Professor Michael Baigent, 57, is a senior psychiatrist and a specialist in addictions, anxiety and depression. Here, he gives insights into his upbringing, family, career and how the coronavirus can affect our mental health.

“My basic advice is to live by the mantra – face your fears”

Can you describe your childhood?

I grew up in Hornsby in Sydney and describing my childhood now, I’m conscious that it sounds romanticised. My grandparents lived next door to us. My father and my grandfather built the house we lived in and I had very close friendships with kids in the neighbourhood. I remember our street before it was bituminised and when we had bush and paddocks across the road. I had a barefoot, adventurous, roaming childhood with my friends – lost in the bush, hunting eels with homemade bows and arrows, setting off firecrackers on Guy Fawkes day and getting up to lots of mischief. When I was really young, the community got together and one of our neighbours would dress up as Santa and come down the street for the kids on Christmas morning. I thought it was the real deal.

My idyllic existence was shattered when my younger sister passed away when I was close to five years old. Anita died from complications of heart surgery. My parents didn’t have a phone, so when she died, the hospital had to call a close neighbour who woke Mum and Dad and they had to go into the hospital in the middle of the night. Anita’s death had a profound effect on my family and I have seen the strength my parents required to get on with their lives. It has helped me see how significant developmental experiences shape people and the enduring effects of loss.

You rebuild but do not forget. Life is precious and precarious. As you grow, and even in adulthood, events shape the way you think and feel. There are layers to us all. Such experiences are not unique to me. I am lucky to have another sister, Janine, who is six years younger than me, very talented and very funny.

What was life like as a teenager?

We ended up moving to Adelaide when I was 12 years old, eventually settling in Tranmere. I was incredibly lucky that a couple of other boys around my age lived in my street. We became great mates. We spent our formative years together — bikes, skateboards, surfboards, girls, driving, studying, weddings. We are all still very close today.

My best teenage memory is of surfing with my friends, which I did on as many of my weekends as I could. Often the best moments were floating about out the back with my mates, waiting for the biggest set waves to roll through.

As a child, I didn’t really have any strong notion of what I wanted to be when I grew up. My parents said that they were happy for me to do whatever I wanted, as long as I was happy doing it but I had to do Year 12.

For a while, I fantasised about just being a surfer, which was totally unrealistic. I developed my interest in medicine in my final year of school, but had entertained the idea of being an architect before then. University was not a common aspiration where I grew up in Sydney but was more so amongst my friends in Adelaide.

Why did you become a psychiatrist?

The idea of being a psychiatrist always appealed. As a young teen, I used to enjoy reading through a psychology book that my father had for a marketing course. I realise now that I have always had a great curiosity about people. I like people and I enjoy trying to understand their drives and thoughts. It’s arrogant to assume that you know what a person is thinking. An educated guess may be possible, but without asking someone what is going on, you won’t really know. I’ve learnt to ask the question and listen hard to the answer. I like to think that I listen more than I talk.

I studied medicine at the University of Adelaide for six years. Then I completed my intern year at the old Royal Adelaide Hospital. Following that I did a couple of years work in various rotations, beginning specialist training in general practice. I particularly enjoyed working for the Drug and Alcohol Services (DASSA), which is where I first learnt about substance-use problems. I took an opportunity to work at Glenside hospital and eventually switched to training in psychiatry.

There is a lot to learn and it can be challenging personally. Developing empathy for the person is critical. It allows you to develop a non-judgemental approach and to understand people’s experience as best you can. I could not work in my field without this.

Finding out about a person in terms of where they have come from is vital to developing empathy. Some people make choices that are difficult to comprehend until you see how they have arrived at that point in their lives and why they are using that way to manage. They may not be aware that it is causing more problems for them than it is solving, which can be the case.

How did you end up specialising in addiction medicine?

At the end of my training, I was invited to apply for a specialist position at Flinders Medical Centre in 1993. The department was headed up by Professor Ross Kalucy, I find states of addiction understandable. There are biological mechanisms and powerful psychological processes (conditioning and thinking patterns) for addiction. I find it interesting learning how the addiction began and understanding the processes that are maintaining it in the individual – their vulnerabilities. This ultimately can be used to help the person recover.

We have developed excellent, well-researched treatments for gambling at the Statewide Gambling Therapy Service that focus on urge extinction. For other people with substance addictions, different approaches are needed. People often do not comprehend that substance addictions can be like a chronic illness — treatable, but prone to relapse.

What has been your role with Beyond Blue?

I found myself as the Chair of the Section of Addiction Psychiatry (later Faculty of Addiction Psychiatry) and in that position co-wrote an addiction psychiatry curriculum and ensured that training in addictions was part of the core training experiences for psychiatrists. I was also involved in training in addictions for psychiatry registrars at DASSA and I do training there for staff in the area of overlap between addictions and mental illnesses.

I was asked to be the Clinical Advisor to Beyond Blue in 2006, which I did until 2011 and I was then asked to join the Board of Directors in 2011 and my term will finish at the end of this year. It has been a privilege to be part of this organisation.

Where are you currently working?

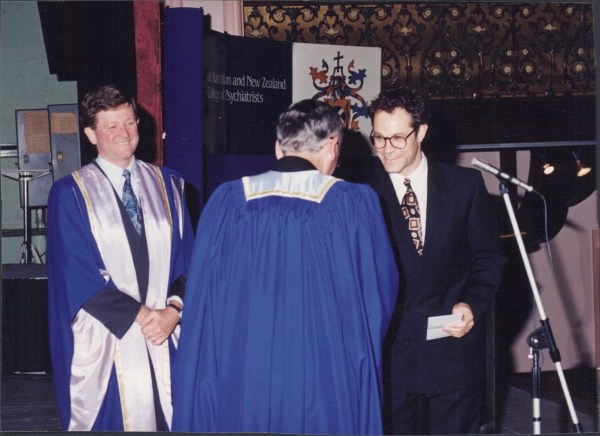

My current roles at Flinders University are Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, Year 3/4 Psychiatry coordinator for the Flinders Medical Course and Exam Board member. I’m currently Head of Flinders Psychological Therapy Services, which includes the Statewide Gambling Therapy Service, the Centre for Anxiety and Related Disorders, and IAPT@flinders. The awarded Statewide Gambling Therapy Service specialises in evidence-based treatment for people with Gambling Disorders and I’m proud of the recognition that this service has received. I’m also a Senior Specialist DASSA, Director of Training in Addiction Psychiatry for South Australia. I’ve won various prizes and last year I was honoured to win the Ann E Loughlin Memorial Prize for my contribution to training psychiatrists.

What forms of addiction do you commonly see?

We see people with all forms of substance addictions at DASSA. There has been a noticeable shift in numbers from heroin dependence to dependence on prescribed drugs. For example, in the ’80s and ’90s most people in treatment who had an opioid addiction, had heroin dependence.

Since then, there has been a significant increase in the proportions of people with addictions to other opioids that are prescribed or obtained illegally and then abused such as oxycodone, codeine, morphine and methadone. The people with these addictions often do not regard their use as a problem until it is too late. I am interested in seeing when South Australia adopts a prescription-monitoring programme, now in place in some other states, if we will see the rates decline and more people find their way into treatment.

How does childhood abuse contribute to addictions later in life?

In my work across all settings, a common unifying thread is a history of childhood abuse – particularly sexual. Abuse that occurred in institutional settings such as the church, is only the tip of the iceberg. People have experienced it within the family or in the community. At its worst, this has a profound influence on personality development and can lead to many problems including substance dependence and it often underpins a Borderline Personality Disorder (although not in all cases in this condition). Eliminate that abuse and I think we could reduce the psychiatric morbidity and demands by a third. The extent of the problem is an uncomfortable reality for the public. They have only just become aware of it since the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse raised people’s awareness.

Having said that, over the last three decades, I have noticed an increase in the awareness of childhood sexual abuse within my profession — the dreadful impact it can have on the mental health, how prevalent it is. When I began in psychiatry, it used to be kept as a dark secret. It was barely discussed or disclosed but the effects on the individual were evident. Now it is part of routine enquiry in histories. It is not more prevalent, but is asked about and more openly revealed. Obviously, this needs to be broached very sensitively.

Tell us about treating anxiety disorders

I’ve noticed improved access to treatment for anxiety disorders. When I began treating people for anxiety disorders in the early ’90s, few people could afford treatment in private settings, so we often saw people with simple phobias. With the expansion of Medicare-based treatments more people can access treatments. As a result, the types of problems I see in our public service are often quite complex. I do think that this is the role of specialist services. I have been heavily involved with Beyond Blue’s NewAccess trial proving the effectiveness of a new service therapy approach for delivering psychological treatment for anxiety and depression. The approach is federally funded now in many areas of Australia and makes evidence-based psychological interventions very accessible via the phone.

Is there still a stigma around mental illness?

Some people with severe psychiatric illnesses need to stay in hospital for a long period of time to achieve stability. There are few opportunities for that as there is constant demand on beds and although community psychiatric care is the preferred way to treat people, it is not enough for all. I have seen ideologies influence planning rather than evidence. We have reduced stigma about mental illness, however, there is a long way to go. It is still quite evident in the language used – some people feel it is stigmatising to say “mental” or “psychiatric” illness/disorders and have created new clunky descriptions to avoid it such as “absence of mental health”, “mental ill health”. I wonder how people would react to describing cardiovascular disease as “absence of cardiovascular health”? The stigmatisation of mental illness and psychiatry is still alive and well.

What is the impact of mental illness on our society?

I have the impression there have been increasing numbers of people who are violent, intoxicated and behaving badly being presented to hospital emergency departments for psychiatric evaluation. There is a misattribution of intoxication or bad behaviour to mental illness. The antisocial and illegal behaviour associated with heavy levels of intoxication with alcohol or a substance, particularly methamphetamines, is a challenging problem for our community and I fear has become somewhat ‘medicalised’, meaning that medical treatments are sought for bad behaviour, and the individual is absolved of their responsibility. People can behave irrationally when intoxicated or sober, but do not have a mental illness. At the state time, when someone does present to hospital with a drug and alcohol related problem, it can be an opportunity to try to engage them in treatment, and change is always possible.

Compared to other disorders such as neurological, respiratory, diabetes, cardiovascular, mental illness is the biggest cause of years lost due to disability. Yet it receives a disproportionately low percentage of health funds. The costs for the services and care that are expected by the community exceed the amount funded. I have seen politicians trying to do their best, however, we could do with more – not only resources, but research for better treatments, and approaches. I have seen refinement in and expansion of psychiatric medications in the last 30 years, but the fundamental mechanisms of action for most of our psychiatric medications have not advanced in 50-60 years. Although our biological treatments help many, there are still people who have inadequate outcomes. Losing patients to the tragedy of suicide is overwhelmingly distressing for all. The conditions we treat can be serious and deadly for some – the risks can be like a heart attack and yet it is often not perceived in that way.

How can a pandemic like coronavirus affect our mental health?

This can have a profound effect on mental health. The uncertainty, fear and isolation each pick up vulnerable individuals. People with pre-existing anxiety disorders can have worsening of symptoms and those who are of a nervous temperament will also struggle.

People have more time to kill and opportunity to drink alcohol if that is a problem for them. The isolation can in itself worsen all sorts of problems for people, for example, those with Borderline Personality Disorders and those with depression.

Elderly people who were alone before can be even more profoundly isolated as the physical distancing prevents even incidental human contact. We often don’t realise they can go for days without speaking to another person to the extent that they may feel the strain on their voice when they do. Obviously, the devastating financial impact can precipitate mental illness and strong feelings of anxiety and despair as a normal adjustment reaction.

I have also seen people rise to the threat, develop more altruism and a sense of common purpose which are very helpful. In our local community, someone started a social media network after a letterbox drop. This wonderful idea has now meant that we are more connected, know names and all aware that one of our elderly neighbours, who is not on the internet, had felt dreadfully lonely for some time and now has people making contact with him (albeit appropriately socially distanced). A community spirit has developed that was not there before.

Have you seen evidence of the mental health effects of COVID-19 first-hand?

Yes, I have seen some anxiety problems heighten, for example, as we have moved to more email and internet communication. The anxiety focused on that form of communication. For some patients with severe Gambling Disorder, we cannot use gambling venues to complete live exposure so have had to modify our approaches, but they are still able to make headway.

Every now and then I see normal anxiety in my health worker colleagues — concerned about their own susceptible family members catching the virus from them, and concerned for the health of the community if the numbers escalate.

How can we combat these anxieties and fears?

The normal anxiety amongst health workers is in some ways managed by remembering our important purpose and role, acknowledging the anxiety but not letting ourselves become overwhelmed by a cascade of catastrophising fears — calling a halt to those thoughts and moving on to something else.

Common sense approaches that everyone knows about will help as well such as making sure there is some enjoyment in your day and distraction.

When there is illness, however, it does require proper treatment and I am pleased to see that in Australia, we are aware of that and I give credit to our health ministers and health planners for their attention to this.

Any other advice you have around coronavirus?

I am heartened and astounded at the improvements that are quickly being put in place in our health system. There is a lot of streamlining and innovation that pre-COVID 19 would have taken months of painful deliberations to get to, but now they are being enacted with efficiency.

Some may prove ineffective, but I suspect many of the changes will remain and have improved the care provided.

Social factors are potent determinants of mental health and I really hope that our demonstration of genuine concern and caring attitudes to each other will have some impact on the burden of mental illness.

What are you most proud of in your work?

I’m very proud of the medical students and junior doctors who I have helped train. I enjoy helping people get over their problems and have seen some remarkable recoveries. This is possible for people with many conditions.

My take-home advice to anyone interested in reducing mental illness is firstly in relation to anxiety disorders: realise that they are fed by avoidance. Secondly, dreadful harm is caused by childhood abuse and trauma and we will prevent a lot of the burden on mental illness if we can put a stop to it. Finally, we need to realise the importance of acceptance, community and family, for mental health.

My basic advice is to live by the mantra – “face your fears”.

How do you switch off?

I switch off by surfing whenever I can and thinking about surfing as well as painting, which I have just started to learn.

My wife, Ruth and I have been married for over 27 years. We have three children, a daughter in secondary school and two sons at university.

Your biggest mistake in life?

Since childhood, our oldest son has been very IT savvy and he begged us to invest $2000 into Bitcoin when it began. We scoffed that it would never take off. Who would follow the advice of their 14-year-old son on investing that sum of money? It would now be worth $3.5 million. Fortunately, I have seen that happiness is not reliant on wealth and our son has learnt forgiveness.