Six decades since they began training as student nurses, this group of women continues to foster a special kinship that has withstood the test of time.

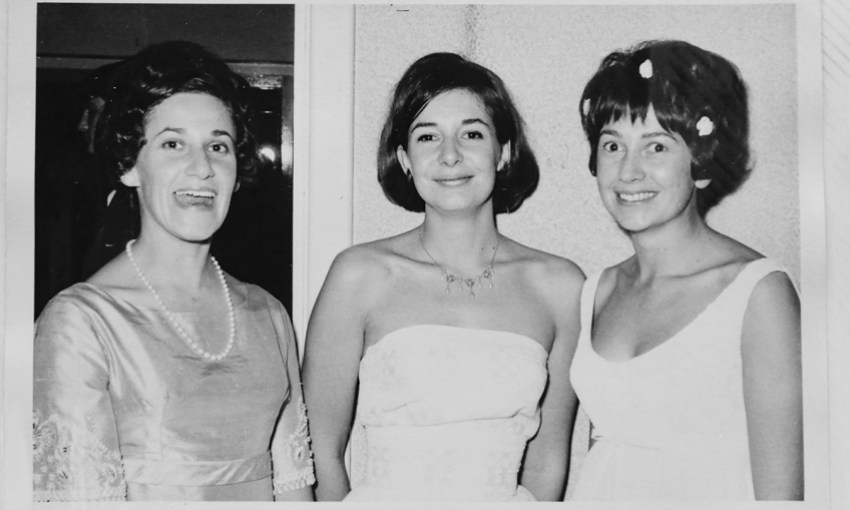

Intensive care: Student nurses in the 1960s

On a gloomy winter afternoon, fits of laughter emanate from a table of 15 ladies lunching at an eastern suburbs hotel. Hugs are exchanged and wine is poured as they settle in for a catch-up that might seem like any gathering of gleeful grandmothers. Except it isn’t; today’s assembly is an extraordinary occasion.

As soon as they see one another, the women are in some invisible way transformed back into the bubbly teenage versions of themselves who, in 1962, first met when they began training as student nurses at the Adelaide Children’s Hospital. The hospital later amalgamated with the Queen Victoria Hospital to become the Women’s and Children’s.

Exactly 60 years have passed since they all moved out of their family homes and into a nurses’ boarding house in North Adelaide. They studied for three-and-a-half years under the watchful eye of a strict group of nurses, referred to as sisters.

Now all in their late 70s, the group – including those who did not finish their training – has stayed in touch ever since and meets at least once each year.

Those who did graduate were given certificates that proudly display The Florence Nightingale Pledge for Nurses, which states; “I will abstain from what is deleterious and mischievous, and will not take or knowingly administer any harmful drug”.

Former nurse Glenys Yap is taken aback as she re-reads the pledge today.

“I think, my goodness, poor Florence would have been horrified at the mischief we got up to sometimes! It was just harmless, but there were certainly some things that we shouldn’t have been doing,” says Glenys.

“The pledge was a very important thing – there was no religion involved but when you qualified, you became a ‘sister’ which was all to do with Florence Nightingale.”

The ladies have the type of friendship that, even after years apart, always picks up exactly where it left off. The discussion bounces from grandchildren to reminiscing about their nursing days, holidays they took together as young women and then fondly remembering four of their group who have since passed away.

In 1962, their cohort began with 24 girls, mostly fresh out of high school. All were required to wear a uniform of white caps and dark-blue capes – which were next to useless for any warmth. Nurses walked in the open air when travelling between wards, which would be bitterly cold on night duty during winter. Even so, they were not allowed to wear jackets or gloves because they didn’t comply with the uniform.

“I remember the Royal Adelaide Hospital nurses wore longer capes and I used to think it’d be so lovely to have a long cape instead of these ridiculous things that were supposed to keep us warm,” says Glenys.

Qualified nurses at the Queen Victoria wore long veils that were uncomfortable to work in and very unpopular among the sisters. When the veils were abolished and replaced with caps – much to the nurses’ delight – a small group including Glenys one night raised a veil up on a flagpole, emblazoned with the words “Rest in peace”. It was quickly taken down in the morning but the incident made the newspaper headlines, “which was horrifying because we should never have done it”.

“Luckily, we were never asked to own up,” says Glenys

Although they learnt respect and discipline that has stayed with them throughout their lives, laughter and a spot of mischief were key to survival. The strictness of some of their superiors, difficult shift work, living away from home and tending to sick children all created a challenging environment in which they formed strong friendships.

“Seeing children injured, burnt and brought in from car accidents was traumatising at times,” says Glenys.

“But after a particularly difficult day, you’d walk across to the nurses’ home in the dark, go up to your floor and then see a light shining under one of your friends’ doors. You knew you could tap on the door and have a chat or a hot chocolate together. You could share a story and sometimes have a cry with them.”

The student nurses boarded in humble rooms on the same floor. They didn’t have telephones, some had radios, and there was a midnight curfew. If they were being picked up by a boyfriend, he had to wait outside or in a sitting room near the entrance.

The girls made their own fun together on their days off. When The Beatles were in Adelaide, a few off-duty nurses went to Anzac Highway to wait for hours just to catch a glimpse of the band driving past in the blink of an eye.

“When I look back, I realise that we were so young. The majority of us were 17 and 18. It was a daunting experience; for some of the country girls I think it must have been really very scary and that’s probably why we bonded so well together. To survive it all, you had to,” recalls Glenys.

Once, Glenys was working on a ward under a sister who had a habit of making misery for the trainees.

“After the last day with her, another girl and I went up to the floor where the sisters lived – we weren’t even allowed to be there and I was terrified – and we stuffed paper into the keyhole of her room so she wouldn’t be able to get in. There was a sense of respect for your elders and that you shouldn’t really do any of those sorts of things, but they happened.”

When in the presence of a senior nurse or doctor, nurses had to stand-to with their hands behind their back, always letting a superior into a lift or room first.

“Some of the sisters were lovely and some of them were not so lovely. When you worked in the ward you wouldn’t just go into the office to see them. You’d tap on the door and be told to come in if you wanted to ask something. You had to show respect,” says Glenys.

At the reunion, conversation sometimes touches on various children that spent time in hospital or some of the cutting-edge procedures that were introduced. One admits that she never really wanted to be a nurse and that she took up nursing because it gave her a chance to move out of home. All of them were “mad for babies” and each had their favourites in the nursery.

As the women catch up on what they’ve been up to over the past year, Barb Marrett speaks up to get the rabble in order – and everyone listens, mostly.

“She’s our matron,” one of the ladies points out.

“I would say mother’s a nicer word,” Barb replies, who is a natural organiser and central to the group’s continued connection.

Barb says that to have such a friendship group of 60 years is a very special thing.

“You take up where you left off. It’s warts and all; who cares what we look like or that we’ve aged? When we meet, we only ever see the good things. We go away thinking, ‘Wasn’t it great to see them and hear about their lives?’,” she says.

Despite losing some beloved friends along the way, they consider themselves a lucky group, and all the more special to remember them.

“Life’s been pretty good to most of us, and I think the secret is to make the most of it while you can,” says Barb.

“Who knows what next year will bring, but we will certainly get together again.”

This article first appeared in the July 2022 issue of SALIFE magazine.