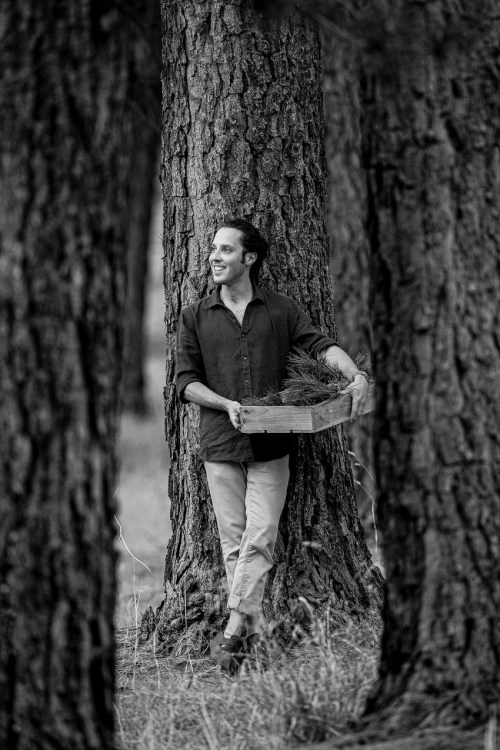

He is inspired by a “sense of place”, a commitment to sustainability and his love of foraging near his home in the Adelaide Hills. Meet SALIFE’s new recipe contributor, award-winning chef Kane Pollard, as he reveals the philosophies that spark the unique dishes he creates.

Pride of place

Kane Pollard walks slowly along a dirt track beside a busy Tea Tree Gully road.

The award-winning chef is oblivious to the cars whizzing by as he calmly reaches down and pulls out what looks like a stringy weed.

“It’s wild celery,” he says, smelling it and handing it to me.

It’s wet underfoot as we continue our casual stroll along the path.

Kane leads the way, a striped tea towel tucked into his back pocket, as we continue to wander past towering peppercorn trees, tangled blackberry bushes and an expanse of suburban scrubland. With each step, what becomes clear is how uniquely this celebrated chef sees the landscape around him.

Where most will see suburban scrub, weeds and trees, Kane sees edible foliage – pine needles, soursobs, nasturtiums, wild fennel and celery – key ingredients bound for his busy restaurant kitchen.

Kane and his wife Adele own Topiary, a 70-seat, award-winning restaurant set within the grounds of Newman’s Nursery in Tea Tree Gully.

It seems incongruous that such a cutting-edge culinary destination is tucked away inside a suburban gardening business, but these semi-rural surrounds are the lifeblood of Topiary. Here, in the foothills, an abundance of natural ingredients grows right on the restaurant’s doorstep, creating produce to plate in minutes.

Kane forages most mornings and is acutely attuned to the natural environment around him.

“It can get a bit dangerous when I’m driving to work through the hills and I look out the window and notice something has started to sprout,” Kane jokes.

“Through foraging you really learn to just stop and take a moment. I learnt to slow down and breathe and take in what’s around me. You could walk past potential ingredients if you’re not keyed in to what’s going on.”

One of Topiary’s most intricate and popular dishes is Kane’s creation, “Lamb in the Weeds”. The chef was inspired after driving past a field and seeing a lamb pop its head out of the clovers. He decided to replicate the scene on a plate.

“I went to the local butcher and with sustainability in mind, instead of just ordering the usual lamb backstrap or lamb rack I asked: ‘What kind of lamb don’t you use or what doesn’t sell?’,” Kane explains. “He said the lamb necks, so we slow-cooked the lamb neck and served it with a seasonal glaze (cumquat or kei apple), then carefully placed petals and leaves on top. The idea is to lift up secondary cuts of meat to give them a ‘high end’ aesthetic.

“It was probably my first work-of-art-type dish and it didn’t need anything else: it had a story. It was a total sense-of-place moment when I took it to the table and talked to people about where it came from. It resonated with guests straight away.”

The ethos behind Topiary is deeply entrenched in Kane’s sense-of-place dining, where authenticity and flavour are centred in seasonality, as well as sourcing locally, with eyes on sustainability and zero waste.

Where possible, food is made onsite and from scratch. That includes butter, bread (fennel and pumpkin seed), fetta, ricotta, haloumi and jams.

“We also make rosemary stalk smoked local fish, crumpets, puff pastry, literally everything,” Kane says.

The 36-year-old chef is driven by traditional methods of foraging, curing, churning and smoking, back-to-basics cooking that is cleverly spun into contemporary, inventive and beautiful dishes where detail matters; garnishes of nasturtium, sorrel, wild onion, sea succulents, young shoots of petals and edible weeds carefully added with tweezers.

“Everything we create is based on how our ancestors lived 100 years ago and how that made the world a better place,” Kane says.

“It was when we opened Topiary that I started to understand that dining is more than just serving something delicious. Not only is it important to have a story behind how you came up with a particular dish, but also the story behind each element on the plate. It’s important to know why it’s there and where it came from.

“Our older clientele love our house-baked bread and butter and jams, it takes them back to when they were kids and reminds them of their mother’s homemade cooking. That’s pretty special.”

As well as foraging the local surrounds, Kane uses local suppliers where possible, building on Topiary’s sense of community and connection with its customers.

Meat comes from local butchers who support local farmers, flour is from South Australian Laucke Flour Mills, fruit and vegetables from the Adelaide Showground Farmers’ Market, as well as donations from happy customers. One regular, Marlene, lives in Inglewood and often delivers her homegrown persimmons, figs, quinces, herbs and salad leaves.

It makes sense then that Topiary is set in a 160-year-old building, with thick stone walls and a thatched roof held up with old wooden beams. Wild fennel and other arranged dried foliage hang from the light fittings, reflecting Kane’s rustic sense of style and artistry.

This historic building, which was originally a house, has been reinvented over the years including most recently as a tea house and then Topiary Cafe. Kane began working in the cafe as a chef in 2011 before buying the business and creating Topiary restaurant.

Everything about this Hills site – and Kane’s journey to get here – has a sense of life coming full circle, a sense of place, family and home.

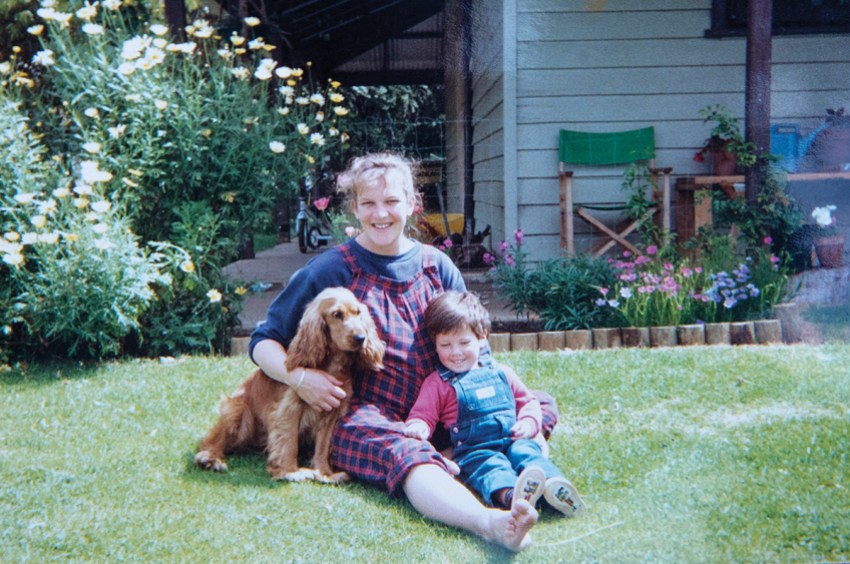

Kane grew up in the Adelaide Hills as part of a market garden family. As a kid, he would get up at 5am and ride his bike to the family’s market garden, harvesting rhubarb with his grandfather Don, and weeding stinging nettles with his bare hands.

“I remember the rich, dark soil and the smell of cardboard because I used to put all the (packing) boxes together,” he says. “It’s later in life that you start to realise what drove you from an early age. My uncle Gavin Pollard was a bit of an inspirational guy at that point, an amazing footballer, and he was starting to take the reins of the business and I knew he was going to be there in the mornings. I loved being around him and my grandfather.”

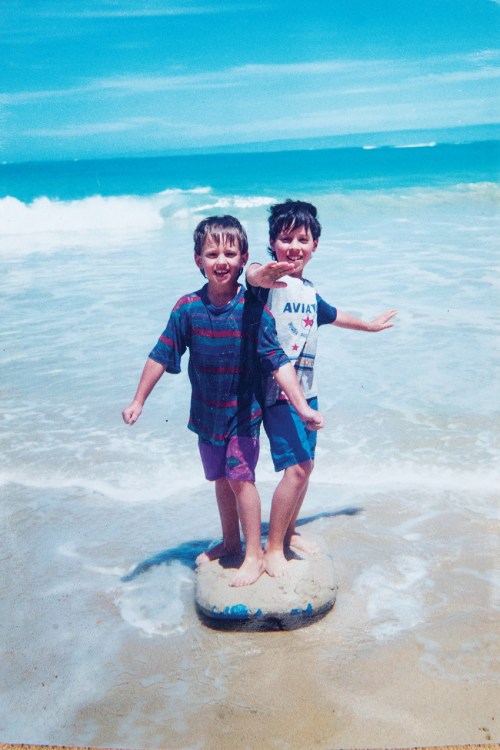

Kane’s parents Kathy and Craig moved for a short time to the small coastal town of Beachport where Kane and his younger brother Cory would go fishing and crabbing. When Kane was aged around nine, his parents separated and Kathy moved back to the Adelaide Hills with her two young boys.

The single mum worked several jobs to make ends meet and Kane credits his mother with instilling his strong work ethic.

“Mum was a very hard worker,” he says. “She worked at the local orchards, cherry picking and sorting and, depending on the season, apple sorting as well.

“Once the picking was done, she’d go and work at the local deli and she also had her own candle-making business at home. I can still remember the smell of lavender in the house.

“It was very much a making-ends-meet type situation. She was extremely tough.”

Friday night was Kane’s favourite, toastie night, when the family would cook toasted sandwiches around the open fire on their cast iron toastie press.

“We’d cook over the fire while mum watched Friends,” Kane laughs.

“We were always renting and they were very old homes in the Hills that got so cold and the fire was the only source of heat, so it was always a bit of a hub.”

Kane admits he didn’t cook much as a kid but, in a sign of things to come, he loved helping to source local produce.

“My brother and I would pick blackberries together, and we’d go to the butcher in Uraidla, the fruit and veg market in Stirling and we’d get fresh seafood in Newton near my grandparents’ house,” he says. “We very rarely spent any time in a supermarket.

“Mum would cook things like tacos, beef stroganoff, fried rice, a variety of cuisines.”

But surely the young teenager must have indulged in some kind of sugary treat, a guilty pleasure?

“My vice was two-minute noodles,” he laughs.

By the time he was at Glenunga High School, Kane says he had no idea what path lay ahead. The school careers counsellor determined a farmer or a chef, so the industrious teenager got his first job at age 15 in a local nursing home washing dishes and serving the meals. It was there that he first experienced the “extreme happiness” that food can bring.

“Because, for the elderly, it was a highlight of the day to gather in the communal dining space,” he says. “The food was really good, cooked by relatives of the residents. Whole vegetables used for soup, like the beetroot with the leaves still on, roasted and blitzed.”

A stint at the Scenic Hotel was his first foray into pub hospitality and the young student would race from school to the iconic Norton Summit hotel.

“It was freezing cold outside and there’s that buzz of a Friday night, the buzz of the dining room, the warmth of the kitchen and I was done with school for the week,” he says. “I remember opening up the dishwasher and the steam would rise up and hit the old window.”

Kane’s first full-time job was at a pub in the city where the young apprentice was thrown in the deep end, washing dishes for six months before even touching food – standard practice for the industry.

Also standard for the industry at that time were some of the unorthodox and at-times cruel methods of initiating young apprentices into life in a commercial kitchen. Kane has memories of having hot pans thrown at his ankles, of being locked in pantries and freezers and regular taunting.

“There was lots of intense, full-on stuff … and I shed quite a few tears. But it was fairly standard, in our little world, it seemed pretty normal. But I think the reason I remember the pan moment so strongly is because I remember thinking to myself that I’ll never be like that. Every time they would do something terrible, I’d think: ‘I will never treat people like this’. But from an educational perspective, I guess it prepared me for the big wide world.”

As he relives some of those painful memories, it’s hard to imagine how this mild-mannered, gentle soul survived the cut-throat nature of commercial kitchens. But it’s his calm, considered nature that enables Kane to do what he does best – quietly observe and learn from his environment.

The pub job provided a good grounding in the basics – steaks and curries and perfectly pan-frying fish. It also exposed the apprentice to senior chefs who recognised his talent and encouraged him to get out of pubs and into restaurants.

The Sebel Playford on North Terrace was the next stop where young chefs were expected to come up with a new canape each night. It was creatively challenging and hard work. Kane says he would often finish at 1am, sleep in his Torana in the car park and be back at work by 5am.

“But it was very internationally inspired and that’s probably where things began to build,” he says. “I was still very young, only 17, and I’d go and buy books in my break to figure out what I was going to do that night. Naked Chef was my first cook book and Jamie Oliver was a little bit of a light at the end of the tunnel, in that he made cooking seem fun.”

An overseas break at age 18 opened doors to more culinary experiences, working in bars and hotels, mainly in Munich, and hanging out with friends who would forage for edible weeds in the nearby Black Forest.

“They used to make fermented liquor out of pine needles, and every morning we’d have homemade dark rye bread with homemade butter,” he says.

Back in South Australia, Kane began acquiring his formal qualifications, studying a commercial cookery certificate. In a step closer to home, he worked in the kitchen at Locavore in Stirling, a tapas and wine bar where everything was sourced from within a 160km radius according to seasonality and quality.

A stint at Salted Vue restaurant in Cairns then reinforced his sense of seasonality and “from-scratch” cooking. But perhaps the most impactful lesson was the waste Kane saw in the fine dining restaurant. Perfect centimetre cubes of vegetables were artistically created, with the rest simply scraped off the chopping board into the bin.

“I couldn’t believe the amount of waste I’d see at the end of each shift,” he says.

By this time, 2007, Kane had met Adele, who was a teacher before she joined the family business at Topiary. It was Adele’s parents, Pelly and Debbie Camerlengo, who went fifty-fifty with the young couple when they were offered the chance to buy the business a decade ago.

As such, there is very much a sense of family around the creation of Topiary. Pelly, a teacher, was nearing retirement and jumped at the chance to be involved in the restaurant when it opened, working front of house for the first few years, while Debbie took on the book work.

Prior to Topiary, Kane also cut his teeth in restaurants such as XO Supper Club and Citrus in Hutt Street, but by 2010 he was ready for a break from the stress and long hours of restaurant life.

“I was still doing 70 hours a week when I saw an ad for a chef at Topiary,” he says. “It was nine to five and they did mainly tea and scones and light lunches. I jumped at it.”

Initially, Kane worked alongside three women in the kitchen; the older staff and the new young chef swapped ideas, skills and techniques.

“They took me in and it was great because I was extremely confident and it was very simple,” Kane says. “But I could see ways to improve the simple things like making our own mayonnaise, sourcing better quality chicken and getting rid of the tinned asparagus used in the vol-au-vents.”

Kane says by the time he and Adele established Topiary, “everything opened up for me”.

“As a chef, you always dream of owning your own restaurant just to have that full creative control,” he says.

But Kane had to move slowly and respectfully, particularly with their loyal, older clientele in mind: swapping a cafe’s tea and scones for a restaurant’s mussels baked with wild fennel, ink and bacon fat crumb couldn’t be rushed.

But gradually, the business flourished, customers stayed loyal and Topiary is now at a point where Kane is able to step back from cooking, leaving the day-to-day to head chef and best friend Alex Payne, and chefs Ashley Cunningham and Leigh Stockwell, who have all been with Topiary for several years.

Having trusted, talented staff to rely on meant Topiary was in safe hands when Kane was headhunted to run Sol Rooftop Restaurant at SkyCity when it first opened in 2020.

It seemed an odd fit in many ways – a foraging, hipster chef with a man-bun taking on a fine dining restaurant at the top of a city skyscraper. But Kane knew he could put this sustainable, seasonal and creative stamp on the prestigious 90-seat eatery.

One of the dishes he is most proud of was his creation “Concrete Jungle”. In line with Kane’s ethos and sense-of-place dining, the idea of the dessert was anchored in telling a story – Kane’s story.

“I went from being surrounded by greenery, foraging each morning, to walking across North Terrace,” he says. “And one morning I noticed this bright green moss growing out of the concrete crack, being driven over, not getting much water, but it was thriving. So, I created this dessert with frozen lemon curd and these green spirals of apple coming out of the top. It was delicious, and divisive, some hated it and some liked it.

“But the whole story it was telling is that I am the moss and I can come to the depths of the city and go to a rooftop and still thrive!”

Within a year Kane had catapulted Sol to a global dining destination with a swag of awards, including the 2021 Restaurant and Catering’s Restaurant of the Year and Best Chef for Kane, who was with Sol for 18 months before returning to Topiary.

“The experience was amazing and I thought maybe I did need to step out of these walls to project what I do from a higher place,” Kane says.

He has stepped out of Topiary again with his next dining project called “Place”. The idea stems from a mushroom forage that Kane does with the Topiary team each year, foraging, cooking and lingering around the camp fire.

“We’ve always tried to create that feeling of using what’s around us in the restaurant, but the only way we can take that further is to take the diner to the destination, so I came up with the idea of ‘Place’,” Kane says.

“We want to create a sense-of-place dining experience, because nothing tastes as good as a mushroom served in the forest where it’s been foraged or a Goolwa cockle dish served on the beach where the cockles have been harvested.

“I’ve always had this dream of establishing a dining experience business where we set up a long table in some of the world’s most stunning locations, places that you would never imagine, and write a menu that reflects the surrounds, working with local producers.”

These days Kane loves cooking, foraging and picking blackberries with Adele and their daughters, Isla, nine, and Maisey, two, just as he once did as a child.

“All of us love to go into the forest together, we do it all through the year, just like I used to do with my brother,” Kane says. “I feel like Jamie Oliver having fun with the kids and teaching them about food and cooking.

“It does feel like things have come full circle in many ways, I feel like I’m home.”

This article was first published in the May 2023 print edition of SALIFE Magazine.