London bombing survivor Gill Hicks is reclaiming her life as a talented artist and performer in a powerful act of healing and harmony.

Gill Hicks: Alive and kicking

Gill Hicks is poised, sitting on stage in a giant black tutu and black blouse. Huge projections of her artworks flash across screens as two musicians, Julian Ferraretto and Dylan Paul, fill the room with moody, atmospheric music while audience members take their seats.

All eyes are on Gill as she begins to sing a slow, hypnotic version of the Bee Gees hit “Stayin’ Alive”. The song immediately takes on new, powerful significance amid the context of this remarkable woman’s life story.

Many will recognise the name Gill Hicks. She is the inspiring survivor of the London terrorist attacks of July 7, 2005. Gill was standing just one person away from the suicide bomber and lost both her legs in the devastating blast.

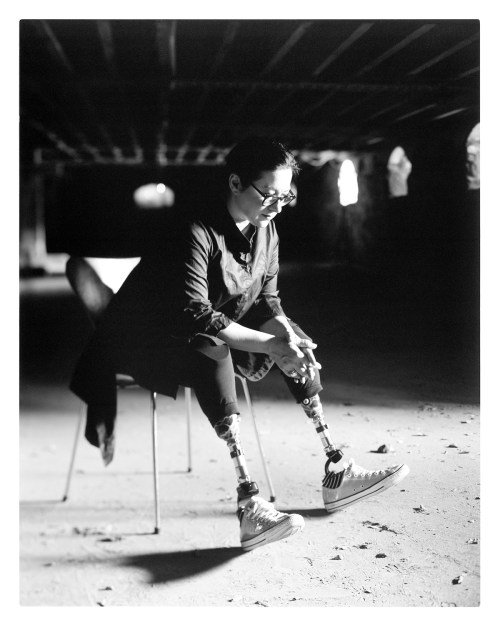

Since then, this courageous South Australian has spent 16 years rebuilding her life, piece by piece. She has had to learn to talk again, how to walk with prosthetic legs and she has endured years of operations and excruciating rehabilitation. The emotional scars are harder to quantify.

But here, on stage at The Lab in Adelaide’s Light Square, one of the most critical components of Gill’s healing is taking place – this globally famous peace crusader is reclaiming her life as an artist and performer.

Before the bombings, Gill’s life was always immersed in the arts. She trained as a jazz singer in her teens, was an avid painter and had a high-powered career in the design industry in London.

But all of these artistic pursuits were sidelined in the aftermath of the bombing, buried amongst the twisted wreckage, as Gill was suddenly thrust into the reality of simply surviving.

Through her show Still Alive (and Kicking), made possible through an Adelaide Fringe Festival grant, Gill has recreated herself as a performer, publicly proclaiming her return as a creative force.

“Being back on stage, singing and using my art and narrative has given me the greatest sense of my full self since the bombings,” Gill says.

“When I first performed the show at Fringe, I came off stage every night and just sobbed. It has been very, very emotional.

“I couldn’t anticipate what I was going to feel, all that rush of dopamine and the endorphins. I was saying, ‘Here I am, here’s my art and it feels good to be with my art again’. I had all these components of the show, but what I didn’t anticipate was how I would feel so complete. I haven’t felt that for 16 years.

“It suddenly didn’t matter that so much of me is missing because I felt whole. It was just extraordinary.”

The show played for 12 nights and went on to win rave reviews, as well as the coveted Fringe Edinburgh Award worth $10,000. Those funds are usually used to stage the winning show in Edinburgh but, with COVID restrictions, the show was instead filmed and projected onto a tower at Edinburgh’s Napier University – a digital triumph of survival and artistic rebirth beamed across the globe.

Still Alive (and Kicking) incorporates multimedia displays of Gill’s paintings, videos, spoken word and singing to convey her astounding story of survival. Her signature series of paintings, entitled Brilliant Tall Poppy and created using her fingerprints, flash across the screens as Gill quietly, powerfully, commands the crowd.

It is at times a harrowing ride as she relives the minutes, hours, weeks and months after the attacks, detailing unimaginable horror and violence. But there are also themes of redemption, hope and beauty conveyed through Gill’s moving narrative.

Gill relives vivid memories of the moments immediately after the blast, as she lay bleeding to death in the darkness, unsure if she was dead or alive. She talks of stretching her hand out into the blackness, desperately searching for something, anything, to anchor her back into life. Suddenly, she felt another hand and gripped it tightly. They were strangers on the Piccadilly line just moments before, oblivious to each other on the morning commute. Now, they clung to each other, a spontaneous and desperate human lifeline amid the thick, black smoke and eerie nothingness.

At that point, Gill wasn’t aware her legs had been blown off. The shock, or some other force, was protecting her from the pain. Then, she says, she heard the “beautiful” voice of death.

“It was female and it said, ‘You have lost both of your legs, this isn’t how you want to live’. That was when I first realised I was a double amputee,” Gill tells SALIFE.

“It was almost this gentle calling, saying, ‘come with me’, and I felt no pain, just such warmth and beauty and I remember putting my hands to where my legs were and being shocked at the verification that what this voice had said was right.

“I was trying to understand it; it’s that strange relationship with the body where the brain is trying desperately to make sense of what it’s experiencing. ”

Then, other victims in the carriage began yelling out their names into the darkness, desperately trying to connect. Sadly, some of the names stopped.

“That reaching out and holding each other, I attribute that to keeping us as best alive as we could but we lost people in that time,” Gill says.

Then a strange sense of calm descended; Gill says she realised she was wearing a scarf, something she rarely wore. She took it off, ripped it in two and tied each piece around her legs to stem the bleeding.

“I remember the security lights in the tunnel came on then, so it was like a dark grey hue because the thickness of the darkness was really something,” she says. “It was almost like a tar; a dark, soupy, thick mass that wasn’t like smoke or anything I’d ever experienced before.”

As she waited for rescuers to arrive, Gill recalls with absolute clarity that a film of her life began to play before her eyes. Suddenly, she was a little girl again playing on the beaches of Seacliff and Glenelg.

“I could actually feel my feet in the sand, it was extraordinary,” she says. “I could feel myself looking up to the sun and how hot it was on my face and in that moment, I was acknowledging the sun. Then, the frame changed and I was having a drink with a girlfriend, laughing and clinking glasses and it was so distorted but so real that I felt instinctively it was trying to say to me that life is in the moments and all I kept thinking was I want more of this film, I don’t want this film to end.

“I thought, now that I know this and I’ve had this realisation, it’s almost like a mantra and I will now be mindful to live very differently, to live in the moments. So, I then made a conscious decision that, ‘No thank you, death, but I want more film’.”

Gill was the last survivor to be rescued from the tube that day and was not expected to live. The paramedic, Brian, who has since become a close friend, reported that Gill was technically dead, but kept talking.

“I know it doesn’t make sense but he yelled out to the ambulance driver, ‘It’s dead but still talking’,” Gill says.

Once they reached the hospital the head of emergency wanted to pronounce Gill “dead on arrival”, but Brian convinced them to keep working on her – the agreed time was three minutes and 30 seconds. At that stage, due to the extent of her injuries, Gill’s identification tag simply read “one unknown, estimated female”.

As resuscitation efforts continued, and they reached the three-minute mark, Gill began to breathe – that extra 30 seconds was her gift of life.

She says Still Alive (and Kicking) is about celebrating that gift and remembering to be grateful for every precious moment – just 30 seconds can make all the difference.

“I think the aim of the show is to talk about life through the experience of death. We don’t often get to do that because we don’t get the opportunity to go to the absolute limits of death and be able to come back and see life through a different lens,” she says

Prior to the bombings, Gill had carved out a successful career in London for more than 20 years. She was running her own design consultancy, Dangerous Minds, and had previously been publishing director of architectural and design magazine Blueprint, as well as head curator at the UK’s Design Council.

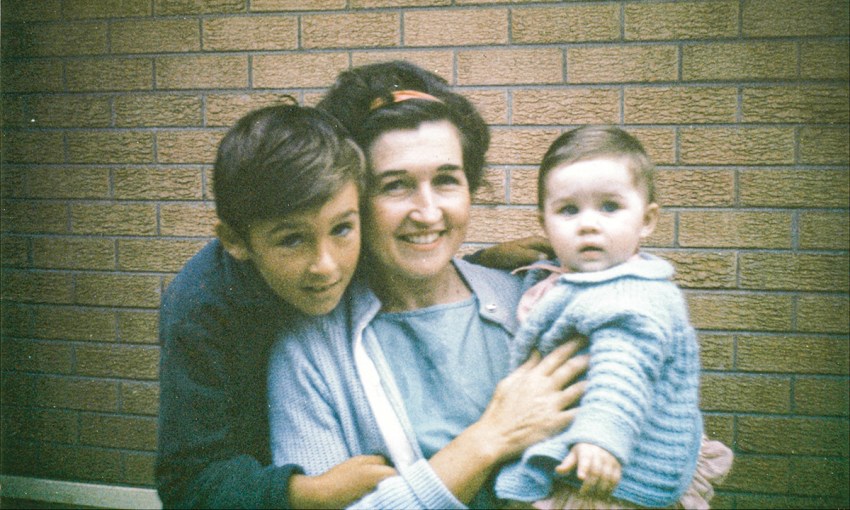

She had made the decision to move to London as a naive 19-year-old, following the deaths of both her parents. Gill’s mother Alison passed away from pancreatic cancer just 12 months after her father Don had died following a heart attack. She says it was just three months between diagnosis and death for her mother, who was only in her 50s.

“She had worked at David Jones in the fashion and accessories department,” Gill explains. “She was one of life’s very soft, sweet people. Mum never had a bad word to say about anyone. She was also a deeply religious person and to see her travel into a knowledge of her impending death; she accepted it with such grace because she felt she was going to God.

“I was there when Mum passed away, so for me to see that acceptance helped me enormously. I was so privileged to be with her at the end and those moments of holding her hand, witnessing her last breath and seeing this fragility of life and death.”

The family had lived in the seaside suburb of Seacliff where Gill spent summer days on the beach with her brother Graham. Back then, young Gill dreamed of becoming a famous singer but was dissuaded by her father, who encouraged a more conventional career path. Still, Gill says one of her fondest memories is being in the car with brother Graham who would drive her to singing classes in her teens.

“It was a very special time because I got to listen to his music in the car,” she says. “He liked iconic bands like Fleetwood Mac, ELO, Pilot, Queen and America.”

Once both her parents had passed away, Gill says she felt rudderless, like she had nothing to lose by plunging headlong into a life overseas, despite knowing no one.

“Mum had been like an anchor in my life,” she says. “I would never have left South Australia had my mum been alive, so, in many ways, it was her death that became a catalyst for so much change in my life.

“My parents had made sacrifices for my brother and me so, when they were gone, I thought I needed to go out into the world and see what I’m made of. That was my driving force; I thought, ‘Okay world, what have you got in store?’”

Little did Gill know the battle she would face as a survivor of the devastating terrorist attack that killed 26 people and shocked the world.

Following the attack, Gill devoted her life to advocacy for humanity and building a sustainable peace. She is a sought-after public speaker and also sits on advisory boards and consults globally on countering destructive narratives. She has also established an organisation called Making A Difference for Peace M.A.D. and says she is driven by “generating collaborative ideas that can challenge narrow ideologies”.

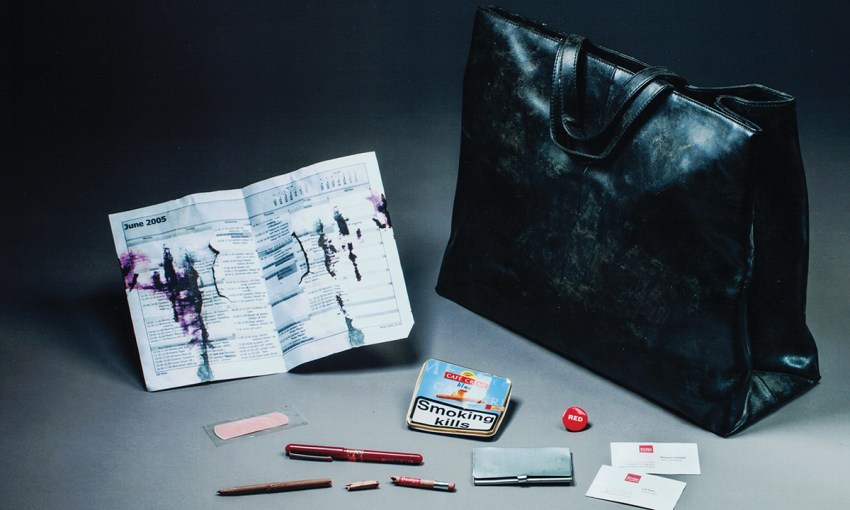

As part of her campaign for peace, Gill has always been unafraid to describe what terrorism looks like close up. She does this in Still Alive (and Kicking), including detailing how the forensic team delivered her bag to the hospital after finding it in the wreckage.

“I opened up my briefcase; I used to smoke these little cigars and they were all pulverised and all my make up was pulverised. It was a mess,” she says. “Then I looked at them and said, ‘You didn’t happen to find my legs did you?’.

“They were shocked because I was talking about it so openly and they said, ‘Yes, they’re at the hospital’, and I said ‘I need to see them, that’s me’.”

A few days later Gill was taken to the morgue to say goodbye to her legs and feet. Her feet were presented on a cushion, and the rest of her legs were bandaged together on a separate sheet.

“It felt so natural because they were part of me. I needed to be able to say goodbye and have that moment of the memory of every bit, because I was always so fastidious about having perfectly painted nails,” she says.

“There were these beautiful, darling feet and I wanted to make sure I felt every toe and etched it in my mind. All the little characteristics they held – that’s something that can’t be captured in a photograph – it had to be in my mind.”

Gill says that goodbye was a pivotal moment because it signalled that what had happened to her was permanent.

“When most of us get sick at least we are given a prognosis and a sense of hope, we take the medication and hope that we will be everything we were and more. When it is a permanent change, and you don’t know if you will be able to walk, you have no bearing of what that could mean,” she says.

“For me psychologically there was this demarcation line. This is an end and now I must start thinking in terms of being given a chance to have a second life, and what do I want that life to be like?

“So, it’s a design process of starting from scratch and having a very new idea of being in the world.”

At its heart Still Alive (and Kicking) celebrates the joy of life, of living in the moment. One of the topics “finding opportunity in adversity” reflects Gill’s incredibly positive outlook, and sense of humour. When it came to having her prosthetic legs made after the attack, she asked if she could be taller (she had been just 165cm before the bombings).

“Maybe it’s part of creating and designing the new life,” she laughs. She ended up being 172cm but when she returned to SA in 2012 the prosthetist suggested she go slightly shorter to reduce the impact on her body.

As she reflects on her life today, Gill is clear on her biggest achievement: the birth of her daughter, Amélie, now eight.

Gill had always wanted children but, after a failed marriage in London years earlier, and years spent learning how to live again after the bombings, she felt her dreams of motherhood were slipping away. But that changed after meeting her partner Karl in 2011.

Amélie was born on January 10, 2013 and Gill says motherhood has surpassed everything she could have imagined.

“I thank Amélie every single day,” she says. “I say thank you for choosing me to be your mum, for enabling me to be a mum.”

As a toddler, Amélie thought Gill was part robot due to her prosthetic legs. Now she is more aware of what happened to her mother and Gill is open about discussing the bombing in the right context.

“What we’ve talked about extensively is that the person who did this made a choice and he had so many moments to change that choice and he still pursued it, knowing the detrimental effects his choice would have on other people,” she says.

“So, we talk about the impact and the importance of making choices and she understands that, she is very politically aware.

“For Book Week at school recently she went as Malala [Yousafzai] – the young Pakistani activist who was shot for going to school. I don’t deliberately expose her to everything but that is the environment she is in and she grasps at it and is fascinated by how the world works.”

On the 10th anniversary of the bombings in 2015, Gill says she wanted to push herself to achieve important milestones. She abseiled down buildings, learnt to tap dance and put on a concert, swam with sharks – and made an emotional return to Kings Cross station in London on July 7.

There have been awards and accolades including receiving an MBE for services to charity in the Queen’s New Year’s Honour’s list in 2009, being named South Australian of the Year for 2015, and being made a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in 2016 “for significant service to the promotion of peace in the community through public engagement, education and network building initiatives”.

But it was being asked by celebrated artist Chris Orchard to paint a piece for a charity auction in 2018 that reignited the spark of creativity. Gill says that as soon as her brush hit the canvas, something “inside of me transformed”.

“I just started painting foot impressions, a mandala of tiny footprints,” she says.

“It was like I was in a trance; like the canvas was saying to me these feet and these footprints are us, this is humanity and this is a body of work that you must do to remind people. It was all screaming at me from the canvas.

“Chris saw it and said, ‘What just happened?’. I said, ‘I’m back’. I haven’t stopped painting from that point forward.”

She was eventually awarded the Ed Tweddell Residency at Central Studios, and has also exhibited her works at SALA for the past couple of years. Gill is also on the board of SALA, as well as the board of the Women’s Playhouse Trust in the UK and Europe, which helps promote the works of emerging female playwrights.

She began singing again when she was asked by local musician Gary Burrows to take part in the Adelaide Music Collective, singing a peace anthem in 2015. The fact that Gill is able to sing at all is astounding, given she is now deaf in one ear and has only one functioning lung, due to the extent of internal burns and injury.

Future projects include working closely with her friend, respected neuroscientist Dr Fiona Kerr, developing a new Adelaide Fringe show called Hippocampus, which references the frontal lobe of the brain.

“It will be an immersive work and we are looking at writing original music and creating artwork that deliberately entices new neural pathways to form in the brain,” Gill says.

Her driving passion has always been to encourage empathy, compassion and understanding as a promoter of peace – only now, she is channelling those messages through art and song.

“What I have realised is that being whole isn’t about the physical, it’s about your spirit and your soul being full,” she says.

“It’s about understanding that perhaps the quest that we are all on in being alive is taking the good and the bad and finding a higher ground.

“It’s not easy but I think it deserves the practice of reminding ourselves daily that if this was my last day, am I happy with how it’s gone and what I’m doing? I think when you are on your right path beautiful things come together and help you continue on.”

Still Alive (and Kicking) can be experienced via Gill’s website musicartdiscussion.com

This story first appeared in the October 2021 issue of SALIFE magazine.