Over the past 18 months, Louise Russell has discovered first-hand the life-changing power of art.

‘My art is reframing my past’

Louise’s urge to take up painting was first ignited by a visit to the Art Gallery of South Australia, where she saw artist Ben Quilty’s series of works inspired by the abandoned lifejackets of asylum seekers washed up on a beach in Greece. She was in awe of the power of Quilty’s art and “how he made sense of his world with a brush”.

After several sessions with an art therapist, she realised painting might help her make sense of her own world — especially the grief and trauma she had kept buried deep inside for decades while raising a family and helping others through her work as a palliative care nurse.

Art proved transformative in a way Louise could never have imagined.

In addition to assisting with her mental health struggles, it evolved as a way to share her incredible story of resilience — a story that began on the other side of the world in the house she calls Number 61.

From Lancashire to Adelaide

“Towards the end of my nurse training, I spent time with the district nurses who were caring for a patient who was dying,” says Louise, explaining how her career as a palliative-care nurse began.

“We were surrounded by the whole extended family and from that moment I thought, ‘This is where I want to be’. I just felt a really strange connection, but I didn’t know why then. I didn’t see the work as difficult. I saw it as incredibly rewarding.”

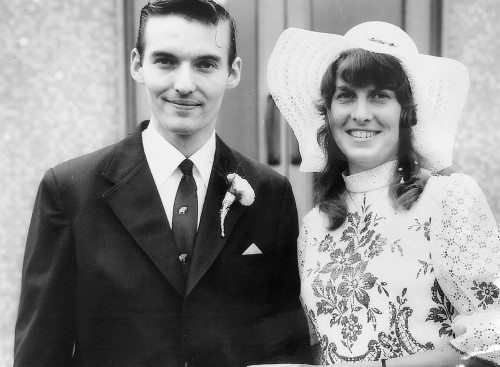

During her training in Lancashire, the county in northern England where she grew up and still lived with her husband Craig and their two young daughters, Louise came to Australia for a 10-week placement at the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

It solidified the family’s decision to emigrate. They believed Australia would offer more opportunities, a better lifestyle and a brighter future for the girls. When Louise graduated, she secured a job at the Calvary North Adelaide Hospital in the Mary Potter Hospice and they moved here in 2008.

Louise admits it wasn’t all smooth sailing in the first couple of years. “But we always said there would be no Plan B. And we really did want to integrate and live the Australian lifestyle and enjoy everything it had to offer,” she says.

Eventually, the family settled into their new life, and Louise moved onto roles with other palliative-care organisations over 12 years.

“I had some really beautiful experiences,” she says. “One that stands out to me is a lady and her extended family. I had been caring for her for some time and had developed a really good professional relationship with them all; I really got to know them. One day I rocked up and their front door was open and I could hear them all singing.

“I just knew she’d died so I waited on the step outside until somebody came out and they said, ‘Come in Louise’, and they just continued singing.

“It was their wedding song. It was so joyful; they were rejoicing the life that she had lived.”

It was only when her role changed two years ago that Louise’s life began to rapidly unravel.

A new rotating roster system saw her working in triage — a job with no patient contact — and she struggled to cope. She was experiencing panic attacks, a low mood, sleepless nights and increasing anxiety.

Louise decided to reduce her hours and her manager tried to expedite a role change, but her mental health deteriorated to the point that she eventually had to take leave.

“I thought it was work; I thought my role was making me unhappy.”

Number 61

Sitting on a sofa by a heater in a corner of the Fleurieu Arthouse in McLaren Vale where she now has a studio, Louise seems adept at blocking out all nearby activity as she quietly recounts how counselling prised open the door to her past.

She had her first appointment with a psychiatrist after being diagnosed with major depression in January last year, and spent most of that session talking about work.

At the second session, the psychiatrist asked about her personal history — and Louise told her everything that had happened at Number 61, her childhood home in Lancashire.

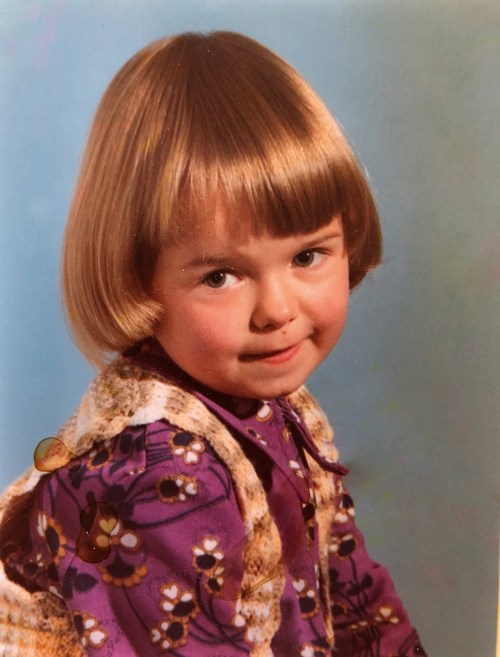

She has happy memories of her early years in a loving family with four girls. But things changed dramatically one Boxing Day when she was just 10 years old and her dad committed suicide.

It was a huge rupture in their lives, but the family never spoke about their grief and loss. Mental health and post-traumatic stress weren’t well understood or acknowledged 35 years ago, and Louise, her mum and her sisters — then aged eight, 18 and 20 — simply carried on.

“I really get the sense that my family were embarrassed that my dad had committed suicide; I was embarrassed to tell people at school. When I did tell them, they didn’t believe me.

“I remember losing a lot of friends and I was bullied at school after my dad died. As an adult now, and looking back, I think parents maybe didn’t want their kids hanging out with me. It was a very tough time for me.”

The family stayed in the same house and around seven months later Louise’s mum met a new partner, who eventually moved into Number 61.

Early on, when they were helping him pack up his belongings for the move, Louise says she recalls feeling that this man was different to her family in some way.

“He changed my mum,” she says. “She was quite an outgoing, extroverted, happy-go-lucky woman and he manipulated and changed her into something that was not true to her values.”

The family home became an abusive and toxic environment. When Louise’s mother did eventually ask for a divorce from her new husband, it ended in tragedy: he fatally stabbed her, her friend from work who happened to be there, and himself.

“I arrived home and my younger sister Heidi was standing in the door screaming and I just knew what had happened. I don’t know how but I just knew … that was the last time we were in that house.”

Louise had already left school. She lived with older sisters for a while before moving into her own rented place in Lancashire at just 16.

Once again, the sisters and their extended family didn’t talk about the tragedy.

Despite all that had happened, Louise managed to forge a good life for herself — she initially enrolled at university to study childcare, then went on to study nursing.

“I’ve always kept really busy. I haven’t stood still for very long; I’ve always had goals,” she says. “I’ve been a big runner and set targets for different events — half-marathons, marathons.”

She also met her husband and started her own family: “They’ve kept me on track, being responsible for somebody else.”

‘I never knew art had that power’

Telling her psychiatrist her family history was the first major step in Louise’s journey in coming to terms with the trauma she had suffered.

“She said, ‘You’ve told me that as if it’s somebody else’s story. You didn’t show that you emotionally connected with it in any way’.”

Counselling helped her understand that working as a palliative-care nurse had enabled her to suppress and soothe her own grief while supporting others through their loss. When she found herself desk-bound, all the emotions suddenly swirled to the surface, clamouring to be addressed.

“That’s what I’ve been managing over the last 18 months – my own grief and loss. I never knew how raw it still was.”

The second important step in Louise’s recovery was starting her art practice. To begin with, she made some paper bowls. It was a way to stay busy and keep her mind calm.

“Managing my depression in the early days was incredibly dark. The days were endless and mornings were the worst. I had made a paper bowl one afternoon and glazed it before I went off to bed. I remember not wanting to get up out of bed because the days were so tough, but that little glazed bowl won me over.”

With Louise’s anxiety still out of control, her therapist suggested she identify some safe places that she could visit outside of her home. One of those places was the Art Gallery of South Australia.

“So I went into the Art Gallery and Ben Quilty had his exhibition on. I was there for hours and I was just in awe of Ben’s work, particularly his work with all the life jackets. I wanted to feel that connection with what I was creating at that time.

“From there I went into the gallery where it encourages you to spend time, colour with pastels and draw your own reflection. I really enjoyed the process. A week later I went back and did it again.”

Once more, Louise’s therapist nudged her in the right direction, suggesting she try art therapy with Adelaide artist Simone Linehan, who ran a class at her Hubert and Mavis studio.

About three sessions in, something life-changing occurred. Louise decided to draw a picture of her dad wearing a gas mask from the war. She knew he had died wearing a similar kind of mask and had long carried with her a vision of how she imagined it looked.

“I was looking at a photograph of him while I was drawing and I was crying.

“It was so cathartic — I never knew art had that power. I was drawing something I had carried with me, and putting it on paper and then having support from my counselling as well … it was like I didn’t have to carry it anymore.”

Later, the art students were given a picture of a skull and encouraged to camouflage it — to create something beautiful out of something ugly.

“I arrived home and I looked at my picture of my dad and I just wanted to make something beautiful out of it,” Louise says.

“I had an overwhelming urge to paint – I used all the same colours from the pastel drawing, and the same shapes, and I painted non-stop until I finished it. Initially, I just started throwing paint on it and then I started to feel it; it was so incredible.

“The feelings I experienced creating that painting were insane, and when I finished, I was euphoric.

“It was the first thing I had in my house from my dad that made me smile. It has reframed things for me and brought me a massive amount of peace.”

Louise named the painting My Beautiful. She went on to create more brightly coloured, abstract paintings that tell her story, yet are imbued with a sense of joy and optimism.

Along the way she made contact through social media with Ben Quilty, the artist who first inspired her to paint, and his responses offered further encouragement.

Louise’s practice over the past year and a half culminated in Empowered, a 2020 SALA exhibition at Fleurieu Arthouse.

“The exhibition is different moments in time throughout the 18 months and the feelings I’ve experienced,” she says. “I think it’s really positive that those feelings aren’t buried anymore.”

The final piece in the puzzle

During her therapy, Louise realised she needed to make a trip back to Lancashire, which she did at the start of this year. Her older sisters were still there, and Heidi — who had emigrated to Canada but was struggling herself — returned at the same time.

Together they finally spoke about their experiences at Number 61. For the first time, Louise didn’t feel alone in her grief.

“It connected us in a way that we have never been,” she says.

“It was really liberating. We’ve all managed our struggles independently of each other and we’ve all seen things through a different lens, so to then come together and talk about it, you can fill some of the gaps from the history.

“As part of that, Heidi and I had a trip down memory lane and we went back to Number 61.”

The two sisters hadn’t seen the house since the night they lost their mother. They felt that returning was an important step in reconciling their traumatic past. The terrace looked much the same from the outside, just slightly more weathered by the intervening years.

“I still had a feeling of dread but it felt like the right thing to do,” Louise says.

“Somebody opened the front door and I thought, it’s now or never. He was a Pakistani gentleman and I went up to him and said, ‘Hi, I’m Louise and this is my sister Heidi — we used to live here when we were little’.”

In a scenario Louise says felt as surreal as it sounds, the trio exchanged pleasantries and then the man invited the sisters inside and introduced them to his wife. The couple and their children had lived at Number 61 for 12 years. They were aware that a woman had died in the home, but not of the circumstances.

Emotions swirling, Louise and Heidi explained only that the woman was their mother.

“I looked in the backyard and on the back wall my mother had had some stone sculptures,” Louise says.

“She’d had about six of them but people kept pinching them so she cemented them on the wall and one of them was still there, but it was broken. I told them about this story.”

The couple invited the pair to return the next day and join them for a traditional Indian banquet.

“We left and as we walked around the corner we just looked at each other and we hugged and cried and said, ‘We’re going back to Mum’s house tomorrow for lunch!’ — it just felt right.

“So we went back and took chocolates and flowers and met their mother-in-law, sister and friend and had an Indian banquet in their back room.”

The couple had even tried, unsuccessfully, to pry the broken sculpture off the back wall for Louise and Heidi.

“They were beautiful, beautiful people,” she says.

“It was like the final piece to the puzzle … the memory we had carried with us all those years of 61 had now been changed by the generosity of that family.

“I look at 61 now and I don’t think of my mum’s murder or my dad’s death. I know that love and laughter continue.

“It’s changed my life.”

Empowered

Louise’s new-found love of painting saw her recently take up a studio space at the Fleurieu Arthouse, so she can devote more time to her art. She is adamant this year’s SALA exhibition won’t be her last.

“I know art will always be a prominent part of my life now because I feel it in my gut; I understand this feeling now.”

She is also passionate about the mental health benefits of art and its potential to help with recovery, which is why she now feels compelled to share her own experiences.

As difficult as the past 18 months have been, she says she feels blessed that she was forced to finally stand still.

“It’s been transformative … my art is reframing my past and changing my future in a way I could have never imagined.”

Louise Russell’s art can be viewed on Instagram @louise.russell.art.

If you feel you need help, you can reach LifeLine at any time on 13 11 14, or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636, beyondblue.org.au

This story first appeared in the October 2020 issue of SALIFE magazine.