The story of South Australia’s gemstone emblem begins tens of millions of years ago and is still going strong in pockets of our state.

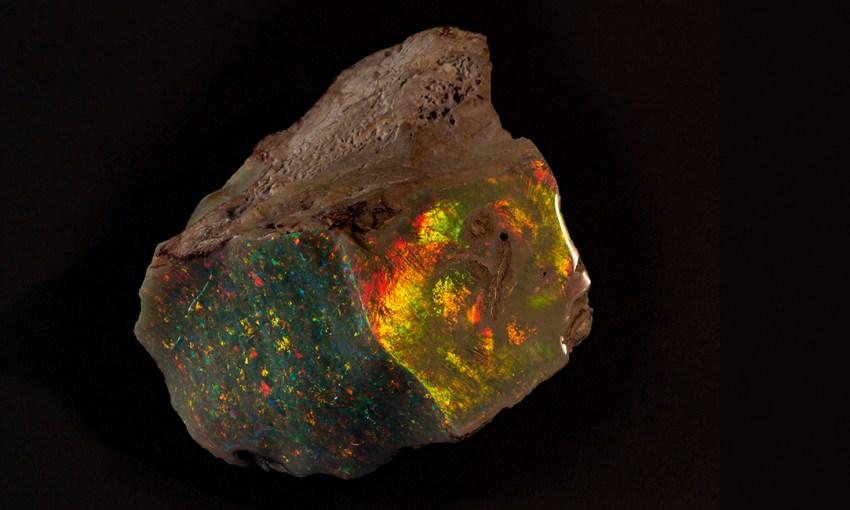

Striking Opal

Ben McHenry knows the greatest legacy he will leave at the South Australian Museum is the glittering opal collection.

Ben McHenry knows the greatest legacy he will leave at the South Australian Museum is the glittering opal collection.

The senior collections manager of earth sciences has been working away in the basement of the museum’s Science Centre for 35 years, where row upon row of minerals of all colours, shapes and sizes are housed in seemingly endless stretches of metal cabinets.

They’ve amassed a staggering number of relics from beneath the earth’s surface, but today, Ben is showing off the jewel in the crown.

The opal collection lives in a safe of its own; $5 million worth of gems behind the door. There are some stunning beauties among them, but no opal can hold a flame to the star of the show, the Virgin Rainbow, a $1 million show-stopper.

“That’s the finest piece of opal ever mined and polished,” Ben says.

It’s hard to dispute. The other opals in the safe are nothing to scoff at, some worth $250,000 alone, but the beauty of the Rainbow is incomparable.

There is no need to light the gem to see its splendour, there’s a certain luminance that radiates from the Virgin Rainbow all on its own. It is only by a stroke of luck or fate that the gem was even discovered and plucked from the red earth to be placed under the world’s spotlight.

If you’ve ever been to Coober Pedy, you’ll know noodling is a popular tourist activity. Mounds of discarded red earth taken from the ground in search of gems dot the landscape. Tourists often get a kick out of sifting through the dirt on the off chance a glittering gem has been overlooked.

Dale Price and Tanja Burk of Tada Opals capitalised on this and built a noodling machine — a giant rotating drum, attached to a transportable shipping container with a conveyor belt running through.

Tanja sits at the belt under UV light, waiting for that tell-tale fluorescent glow that announces an opal had been found.

“They’ve got a really good business model,” Ben says. “They’re always looking for the big discovery, but they realise there’s a lot of money to be made in tiny opal chips. It’s the stuff that gets sent to China for jewellery — that’s their bread and butter.

“So she’s sitting there at the conveyor belt and this tiny little flash of white went pass. She saw it just as the rock that it was in was about to go in the dump. She reached over and grabbed the rock and put it aside.”

The tiny fleck Tanja spotted was the minuscule part of the Virgin Rainbow that was visible. The rest was encased in sandstone and it wasn’t until it was freed and polished that its brilliance was revealed.

At the time, the pair were working in a partnership with another opal hunter, John Dunstan, who bought Dale and Tanja’s share of the Virgin Rainbow.

John brought the opal to the museum a decade after it was discovered and Ben could hardly believe his eyes.

Ben, an expert minerals, fossils and meteorites examiner for the federal government, says it was imperative the opal didn’t leave Australia.

“I have the power to grant export approval for things I’m an expert in and there is federal legislation that prohibits the export of cultural items.”

With the help of a grant from the federal government, the museum acquired the opal.

The Virgin Rainbow is so brilliant compared to other opals because it’s an opalised fossil, rather than just a seam of opal. This means that millions of years ago, when the opal was forming, the silicon dioxide and water had the relatively large, unobstructed cavity of a belemnite (a squid-like creature swimming the Eromanga Sea 100 million years ago) to work its way into.

It might be the collection’s — and the world’s — most impressive opal, but there are other pieces in the opal safe that are important in their own right.

Over the past financial year, Ben received $1.3 million worth of opal donations from the public. Ben puts this down to the great reputation the museum has in the mining world.

“Most of the donations are from opal miners — I’ve developed very good relationships with the opal mining community,” Ben says.

He held an exhibition in 2015, and it was the perfect opportunity for the miners to show off their finds with an independent third party.

“The problem with the opal business is, it’s all individual miners. You can’t really mine for opal on a large scale, so it’s just people down a hole with a pick. They’re a secretive bunch; they don’t want people to know they’ve found opal in case they jump their claims or go moonlighting at night to pinch their claims. They’re all very secretive and they don’t get on very well together. They can’t play in the sandpit nicely.”

The exhibition was held to celebrate the centenary of opal being found in South Australia, and he says it very much worked in his favour because all of the miners wanted to outdo each other to show off their finds, so they put some beautiful pieces forward.

Initially, Ben wasn’t much of an opal fan, but they quickly consumed him.

In the safe, there’s a little box marked “McHenry”. It’s an opal close to Ben’s heart. While he was designing the exhibition, Ben’s mother passed away so he went to clean out her home. “There were a couple of pieces of opal jewellery, mostly tacky 1970s white opal, but then there was this box. I opened it up and there was this gold brooch with a little opal set into it.”

In the safe, there’s a little box marked “McHenry”. It’s an opal close to Ben’s heart. While he was designing the exhibition, Ben’s mother passed away so he went to clean out her home. “There were a couple of pieces of opal jewellery, mostly tacky 1970s white opal, but then there was this box. I opened it up and there was this gold brooch with a little opal set into it.”

He discovered the Victorian ladies’ brooch was the oldest piece of Australian opal jewellery he knew of. There was Ben, working away on this exhibition, completely unaware that his great grandmother once owned the rare piece.

Also in the collection is the Fire of Australia, the world’s most valuable piece of rough opal. That one currently sits in the mineral gallery, but Ben’s visions are even broader.

“I want to tell the story of opals in SA. I still dream that one day I’ll have an opal gallery, not just a case of opals in the mineral gallery.

“I’ve been acquiring things before and since the exhibition, and it’s come to $5 million dollars — admittedly two million of that is in two pieces.”

Ironically, the museum isn’t able to showcase its most brilliant and valuable opal because of the costs involved. The Virgin Rainbow would need a secure case; one with a turntable and lighting, if it’s up to Ben.

“Obviously I’ll have to find a way, because I want to display them,” he says.

This story first appeared in the September 2019 issue of SALIFE magazine.