The advertising industry of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s was a competitive, male-dominated landscape where denim suits, long lunches and catchy jingles ruled.

Adelaide’s Mad Men

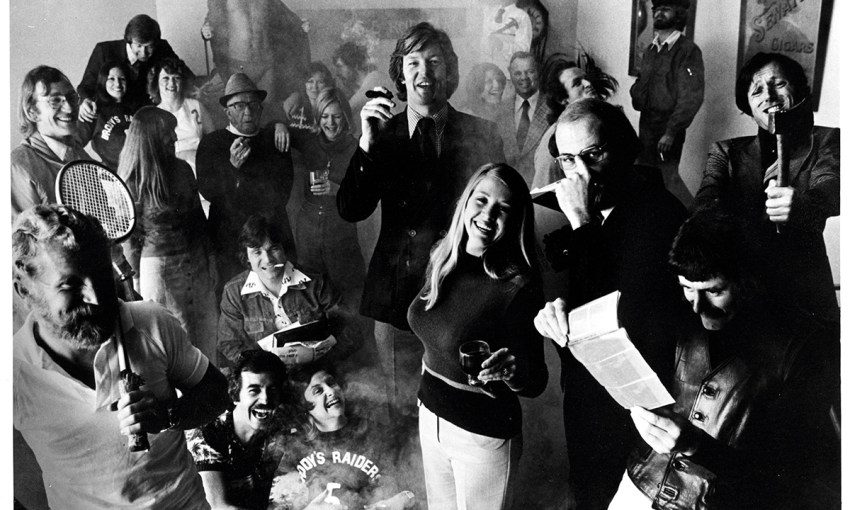

The elite of Adelaide’s advertising industry gathered at the Old Lion Hotel in North Adelaide for the Annual Art Directors Awards.

Executives in high-waisted, flared pants (mostly pink and white), paisley shirts and heeled boots, peeled out of their six-cylinder status symbols — Chrysler Valiants and Valiant Chargers — cars made locally. One colourful character arrived on a camel, but perhaps the most legendary of all was the executive who slid up to the podium to accept his award wearing his socks — only his socks.

Welcome to the golden years of Adelaide’s advertising industry. The annual awards symbolised the excesses and extremes of what it meant to be part of Adelaide’s vibrant and thriving advertising industry through the ’60s, ’70s and into the ’80s.

The air was filled with optimism, success and cigarette smoke, (Ardath, Alpine and Escort,) as Adelaide’s own Mad Men pitched their ideas and sealed the deals over long, boozy lunches.

Local firms including NAS McNamara, Martin Kinnear Clemenger, Taylor O’Brien and George Patterson, the biggest Australian-owned agency, jostled with the international heavyweights of the day.

Companies such as Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB), Ogilvy & Mather, McCann Erickson, Leo Burnett, J Walter Thompson and Foote, Cone & Belding (FCB) all had Adelaide offices, each employing between 30 to 80 people.

The birth of live television and radio, combined with a flourishing manufacturing sector in Adelaide, set the scene for hugely successful advertising campaigns that ran across newspapers, radio, billboards and television. It was a time when Adelaide celebrities including Roger Cardwell, Ian Fairweather, Kevin Crease, Lionel Williams and Anne Wills were becoming household names via the telly. Nationally, celebrities such as Bert Newton and Graham Kennedy were cementing their place in television history with their daring, double entendre gags and ad-lib live ads that had Australians falling about laughing on their vinyl couches.

Australia was shaping its own unique brand of media and entertainment, and at the heart of it all was the booming advertising industry.

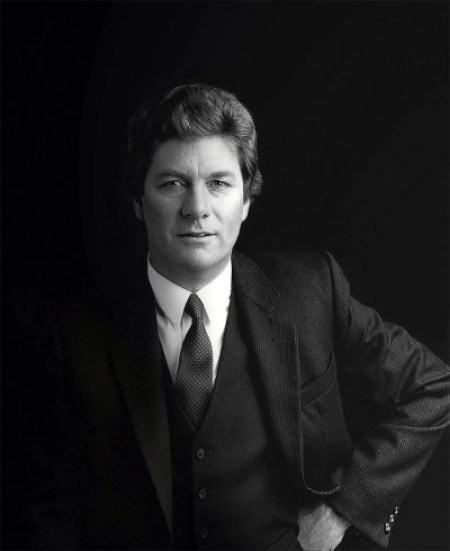

In 1959, a young musician named David Fuller was forging a star-studded career amid all the excitement in Melbourne. Having left school at the age of 16, the young singer/musician formed The David Fuller Trio, and became a regular feature on In Melbourne Tonight, which ran five nights a week. The group also performed Australia-wide in nightclubs, cabaret venues, jazz clubs and even did a six-month season in vaudeville at the famous Tivoli Theatre in Melbourne and Sydney. The trio disbanded four years later and, at barely 20 years of age, Fuller was handpicked by Channel Nine to become the agent in charge of securing the talent for its entertainment shows.

From there, Fuller went on to become a talent agent, representing many of the biggest names in the entertainment industry in Melbourne. He lists the Bee Gees and Peter Allen in his talent pool list.

“I once booked the Bee Gees for two weeks in Melbourne. Eight shows per week plus TV spots for the princely sum of $190 per week,” he says.

Then, at the age of 25, Fuller moved to South Australia and embarked on a whole new career: advertising. The ambitious young man started out at Taylor O’Brien in 1970, before moving over to Martin Kinnear Clemenger as general manager in 1976. Fuller says, back in the ’70s, Adelaide was brimming with clients looking for great campaigns.

“Agencies were always pitching for every client in the phone book, irrespective of their current agency arrangements. It was a very progressive, amusing, interesting business,” he says.

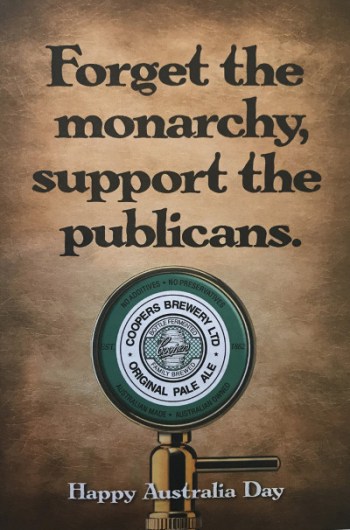

The industry was rich and rewarding, and fiercely competitive, with agencies vying for big local brands such as Chrysler (later Mitsubishi), Simpson, Coopers Brewery, State Bank and other beers, banks, insurance companies and fast food chains that were locally based.

Fuller had a close relationship with Coopers Brewery, his first client at Taylor O’Brien in 1970.

“The marvellous part about Coopers was they could afford to be totally different,” he says. “We could persuade them to do work that others wouldn’t even think about.”

“The marvellous part about Coopers was they could afford to be totally different,” he says. “We could persuade them to do work that others wouldn’t even think about.”

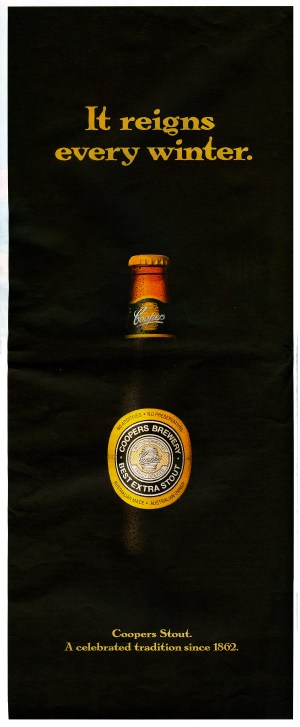

He recalls his first campaign for Coopers Stout where a full-size Cobb & Co coach was built, a team of horses hitched up and then university students were employed to move it around the city.

“They were all dressed like Ned Kelly and they’d rock into the front bar of a pub, guns drawn, and force everyone to drink Coopers Stout,” Fuller says.

“I wrote the television commercial and the jingle, which was recorded at Pepper Studios with Roger Cardwell in full voice, while the Cooper gang robbed the stagecoach of stout on nightly TV. It was completely off the rails as far as beer advertising but it was enough to create a real point of difference.”

The ad for Coopers Stout and lemonade — “mix them up, you’ll be amazed” — was a stick-in-your-head jingle that was another of Fuller’s early efforts. It was recorded for a cost of $720 and ran for six or seven years.

“Apart from my early creative efforts at Taylor O’Brien, the move to Clemenger in 1976 created a partnership with Andrew Killey. My job was to run the agency, which I did for 30 years as managing director. No more ads from me, I was working with the ‘A’ team across the board.”

Respected Adelaide ad man Andrew Killey has a similar story to Fuller. He was originally from Sydney and was touring with his band The College Men in the 1960s when he fell in love with and married an Adelaide girl, Pauline Sheridan. Killey’s brother, Kevin, a journalist at 5AD, introduced him to the station’s general manager, legendary media man Jim Sutton.

“He got me an interview with the advertising company that 5AD, Channel Seven and The Advertiser used called NAS McNamara,” Killey says.

“I started literally at the bottom, filling the grog cabinet, getting everyone’s lunches, riding a bike from Greenhill Road, where the agency was, into The Advertiser and The News with advertising material and riding it back. You worked your way through the different departments until they found out if you had any ability.”

After a few departments, things weren’t looking good for Andrew, until he tried his hand at copywriting. It turned out to suit him because he was “reasonably good at English”.

His big break came when local ice-cream company Amscol needed a jingle and Andrew’s boss couldn’t find the right tune.

“He looked at me and said, ‘You’re in a band aren’t you?’ Write me a jingle tonight’,” Killey says. “I came back the next day with my guitar and sang it to him and he said, ‘that’s good, come and play it to the client’. So, quick, bang, we got in the car and drove to Amscol. I was trembling.” Turns out the Amscol boss liked it too and Andrew had found his creative niche.

“That was my break, I was 19 years old,” he says. “I was writing brochures, catalogues, live radio and TV scripts, as well as recorded versions. It was a very copy-intensive time but you really learnt the business and you got to work in studios, with film companies, with the newspapers and start to understand the whole industry.

“It suited me because it was creative and diverse. I still reckon advertising suits people who have a low attention span and an almost child-like approach to investigation and fun. That’s the way it was. I was there in the best of times.”

Over the years, Andrew worked his way up, eventually jumping ship to Martin Kinnear Clemenger, which became Clemenger BBDO. He went on to become a ground-breaking creative director, and has been referred to as a “brave bugger” by his peers in the industry, thanks to his bold ideas and willingness to take a risk. He and David Fuller forged a tight, creative working relationship at Clemenger for almost 15 years, and Fuller is full of praise for his former colleague.

“Andrew had a wonderful ability to bring things off the research table down into the real world,” he says. “He created some of the best advertising in Australia because he was very good at the idea of ‘don’t be ordinary or predictable’. Think of something you want to say, but say it in a way that hasn’t been said before.”

Killey was behind iconic campaigns such as Snappy Tom “The cats of Australia have made their choice”, and he and his team created the State Bank’s legendary “They don’t have fritz in Sydney” commercial.

Killey says he always tried to be honest with clients “without being rude”.

“The history of advertising is riddled with people with big egos and opinions who were dismissive of the client in the golden years. I’ve always found that a bit repulsive,” he says.

“But if you really believe in something, you’ve got to push it through as hard as you can. I would always say to the client, ‘look, I reckon this is the right way to go, but it’s your money, so at any time you can say we’re not doing it. I think you’ll be wrong, but it’s your money’. When you say that you’re not just trying to sell the idea, you genuinely believe in what you’re putting up.”

They worked hard and played hard during these days, where wining and dining was often a “trojan effort” says David Fuller.

“You’d start at lunch and you may still be there at dinner. We used to say we didn’t have a long lunch we had an early dinner,” he laughs. “It was invariably a fairly wild time. It was the ’70s and everything that went on in the ’70s played out in the offices of the advertising industry, pretty well.

“The business of advertising is essentially about three things. The primary objective is to win the account, the secondary objective is to make sure you hang on to the account and the third objective is to make sure you do ads that are interesting because that will help objective one and two. So, the need for a hefty lunch was prompted by the need to fulfil those objectives. It was usually with clients or prospective clients, plus various members of the media sales department busily trying to flog their space or air time.”

Regular haunts included the legendary Chesser Cellars, La Trattoria, Deckers, Cork & Cleaver and the Arkarba Steak Cellar.

David Minear was just a kid in the 1960s but he remembers his father Harold, one of Adelaide’s most respected advertising identities, working for high-profile Adelaide firm NAS McNamara.

“It was a very collegiate gathering of people and a really happy time,” he says. “I remember my parents having lots of parties in the ‘60s and how it all came together. Dad was writing live commercials for a TV show called Adelaide Tonight. The scripts would turn from 60-second commercials into three-minute skits; it was very common that would happen. So, he was always writing and creating and it just fascinated me.

“Dad didn’t really bring clients home, we had eight children in our family so it was a bit chaotic, but he did bring his workmates home after the pubs closed at 6pm. They didn’t drink martinis but I remember strange things like Chesser Cellar vermouth, hock, lime and lemons and lots of beer.

“There would be chaos and laughter and carry on; it was a wonderful and creative environment. As a 10 or 12-year-old, I remember thinking ‘who are these guys?’.”

At the age of 18, David dropped out of teacher’s college and embarked on his own advertising career. One of the early jobs he landed was as a junior in the Adelaide offices of Young & Rubicam (Y&R) in the mid ’70s. “I was literally working in a cupboard,” he laughs.

Y&R was a huge US firm, based on Madison Avenue in New York. When it opened its doors in Adelaide in 1970, industry insiders agree it upped the ante on the local landscape.

“The guys who came to town were larger-than-life Americans. They were big baseball-bat-cigar-smoking kind of guys with accents and attitudes,” David Minear says. “They’d sit around a restaurant and were very Mad Men-esque in their behaviour,” he says.

“They had a take-no-prisoners attitude. They got the Chrysler business from FCB, the local agency, and then built in other brands like Orlando. The interesting thing for me was that it was a moment that changed the landscape. People like printers, photographers, graphic designers, video people, they all had to lift their game as well. It actually brought international standards and attitudes to the town — and that was really big.”

Andrew Killey agrees that Y&R “reset a higher standard for Adelaide” and all local agencies felt the pressure.

“Suddenly, you either had to catch up to them and be better than them, or they’d get all your business,” he says. “That was when I was at Martin Kinnear Clemenger and it was always the desire to see ourselves as being, not an Adelaide advertising agency, but an advertising agency based in Adelaide.”

David Fuller says briefing an agency creative team could be daunting. The shortest creative brief he remembers was when his team at Clemenger was given the Coopers Sparkling Ale campaign.

David Fuller says briefing an agency creative team could be daunting. The shortest creative brief he remembers was when his team at Clemenger was given the Coopers Sparkling Ale campaign.

“How do we sell a drink that is full of bits of stuff that looks like floor crumbs, floating in a bottle of water from the dam?” Fuller asks.

“We tell everyone it’s beer and it’s special. The result was ‘Coopers Ale — Cloudy But Fine’. We thought that might just work and it did.”

The late Roger Lloyd was another of Adelaide’s respected advertising executives back in the day. His career started in 1960 at McCann Erikson before he joined the Eric Ring, Jackson Wain agency. Lloyd eventually headed up the local Leo Burnett agency in the early 1970s and his daughter Megan remembers going into his Halifax Street offices as a child.

“This was a creative, fun place with a lot of energy,” she says. “We used to be given little jobs such as cutting out and pasting clients’ print ads into giant scrapbooks.”

Leo Burnett’s clients included Hardy’s Wines, Mr Juicy, Dairy Vale, SGIC, Mitsubishi, Woolworths and Hallett Bricks. KESAB and The Birdwood Mill were also on the books and Megan, her sister Christine, and their mum, Judy, were called on to appear in the television commercials.

Megan went on to become a journalist and then editor of the Sunday Mail, influenced by the media she was so immersed in as a child.

“The thing that had the most impact on my life was that our house was just filled with media, every newspaper, every magazine, we always had TV news on at night, and I really think that was why I became a journalist,” she says.

“We had Time magazine, The Bulletin, POL magazine, our living room on weekends was just wall to wall newspapers and magazines. When I woke up in the mornings before school, Dad would have The Advertiser spread out, because it was a broadsheet back then, in the kitchen, smoking a cigarette, having a cup of tea looking for his clients’ ads.”

Leo Burnett also handled the 1977 State Election, devising Premier Don Dunstan’s successful advertising campaign.

Megan recalls the night someone important came for dinner when she was 10 years old. She answered the door in her dressing gown to see Don Dunstan and one of his staffers on the doorstep.

“I knew who he was from television and it was like, ‘Oh wow’,” she says. “Dad introduced us and then my sister and I were sent to the family room while they ate in the formal dining room.

“We also went to a lot of the filming for the television campaign commercials and I remember we went to shoots at Flinders University and down at the beach.”

Nationally, the 1970s were a time of fresh, funny, feel-good television commercials that tapped into the Aussie psyche. At the forefront was legendary firm MOJO, run by Allan Johnston, who hailed from Adelaide, and his partner Alan Morris. The duo created unforgettable campaigns such as Meadow Lea’s “You oughta be congratulated”, Toohey’s “How do you feel?” and later the World Series Cricket campaign “C’mon Aussie, C’mon”, as well as the Australian Tourism Commission commercials featuring Paul Hogan.

It was an exciting time to be in the advertising game across the country, and Adelaide was making its own mark locally through its campaigns and creative characters.

One of those characters was Street Remley, who was one of the original Detroit crew who came to set up Y&R in Adelaide. He fell in love with the place, decided to stay, and eventually left Y&R and set up his own sound company, Street Remley Studios, servicing the advertising industry.

“This place was a hot bed for great production values and creativity,” says David Minear.

“Then there were similar things with Idris Jones who ran Grapevine Studios in the late 1970s and early ’80s, so all of a sudden we have this capacity where people are coming from interstate to do their work in South Australia.”

Minear enjoyed his own success, eventually becoming creative director and then managing director of Y&R.

He says being in the creative department in the ’70s meant wearing denim; lots of denim, including denim suits and ties.

“You weren’t creative unless you wore denim,” he laughs. “Every time I saw my mum she asked me if I still had a job dressed like that.”

Minear remembers Chesser Cellars in particular as the place to lunch and describes it as “one of the greatest places on the planet”.

“I just couldn’t believe that world,” Minear says. “It was a who’s who and what’s going down, it was all there.

“Just the casual nature of the food, having a drink at the bar first. At a time we were watching our weight, thinking a salad sounded like a good idea, but eight bottles of red, too, thanks very much.

“When our secretaries would say, ‘When will you be back from lunch?’, we’d say, ‘Friday’.”

Looking back on the golden era of advertising in Adelaide, Minear says the key to those great ads was, and remains, “impact and cut-through” to get noticed.

He cites a television commercial he wrote and produced in the mid-’70s for Lion Tea Bags as one of his personal favourites.

“It featured a 12-week-old lion cub prowling through a studio floor full of china cups, saucers and teapots, stomping on them, up-tipping and breaking them,” he says. “It was cute in the extreme. The end voiceover was, ‘Lion Tea Bags, a smashing good cuppa every time’. For me, that was an important ad because it helped me get my job as a junior copywriter at Y&R Adelaide.”

Years later, in 1981, David and his art director partner won a competition with their ad for Sigma cars. It featured a priest looking to the skies standing next to a Sigma jam-packed with people with the slogan “Amazing Space”. The prize for the competition was lunch in London with the creative director of Collett Dickenson Pearce (CDP), London’s top agency.

Over the years, various creative teams at Y&R Adelaide produced a number of other memorable ads including Chrysler’s “Hey Charger”; “Sigma — It’s A Sensation”; Mitsubishi Canter “Not So Squeezy”; “Where do you hide your Coolabah?”; West End Export with John Swann and the West End girls and “Boys Light Up” for West End Light.

“At Y&R worldwide, we had a challenge to ‘resist the usual’, which drove our creative work,” Minear says. “It was the test we applied to all of our work. Good enough is not great enough.”

There was just one massive failure: the launch of Dr Pepper soft drink in Australia, a campaign Minear worked on during a stint at Y&R Melbourne in the mid ’90s.

“It was big money, a big budget and the commercial took the Statue of Liberty from New York and moved it underwater and it popped up in Sydney Harbour,” he says. “It was a big ad and holly hell that was very Y&R America and of course the product died. Millions of dollars were spent on advertising and taste testing but people hated it.”

Y&R shut its Adelaide office in 2003. These days, at 67, David Minear is retired from the advertising business and runs his own surf music label, Bombora, and he is also chairman of the Adelaide Fringe. History is repeating itself as Minear’s son Matthew recently established his own advertising agency, BAD, as in brave and dangerous.

“No consumer is safe in South Australia,” Minear jokes.

In 1991, Andrew Killey left Clemenger to set up his own agency with former colleagues Peter Withy and Lyn Punshon. Killey was 41 years old and figured if it all failed, he’d have time to financially recover. He put the idea to Peter Withy over lunch at The Bangkok in Rundle Street.

“I said, ‘Our ethic will be to have fun, do great work and make a fair profit’, that was the business plan. It doesn’t get any deeper than that,” he laughs.

The company, KWP!, went on to enjoy great success, eventually securing the Coopers campaign and devising cutting-edge commercials including “Love Handles” (showing beer tap handles) and “The Dark Side of the Family” for Dark Ale. Even more risque was the campaign for Banana Boat sunscreen, which featured a tube of cream coming out of a man’s bathers with a woman’s hand lunging for it, and the slogan, “get your hands off my banana”.

“We laughed our heads off,” Andrew says. Other clients included Yalumba (the campaign for Jansz), South Australian Tourism Commission (the award-winning ‘Be Consumed’ Barossa Valley ad featuring Nick Cave’s Red Right Hand), the RAA ads featuring “George and Trev” and Vili’s Bakery.

“People don’t sit around waiting to see the ads,” Killey says. “You may as well make them laugh or make them cry but yelling at them like this Haggle stuff, I just think it’s rubbish. Advertising is about creating an emotional connection with people. Good advertising is aimed at the heart, not the head.”

At 72, Andrew continues his creative work through Brand-A, his marketing communications consultancy.

“This work-life balance thing is predicated on the thought that work is somehow a drudgery and I never found work that way,” he says. “It was part of my life and it still is. I love work.”

This story first appeared in the May 2020 issue of SALIFE magazine.