The families that underpin the Limestone Coast’s southern rock lobster industry have steered through troubled waters and are working towards a sustainable future.

Catch of the day

SALIFE finds Craig “Slim” Reilly standing in an aluminium tinnie on a boat trailer. It’s 5.45am and he’s decked out in gumboots, old track pants and a red life jacket; illuminated only by the artificial glow of a nearby streetlight.

The main street of Beachport is barely 250 metres long, so even in the early morning darkness, it wasn’t hard to find our meeting point next to the pharmacy where you can procure some anti-sea-sickness tablets, Kwells. “We sell a lot of these,” the chemist said the previous evening with an all-knowing assurance.

But Slim’s not worried. “It’s going to be a good day out there,” he says while he loads the tinnie. It’s hard to believe, given the previous day’s howling winds, so sea sickness tablets seem a logical precaution for 10 hours of riding the Limestone Coast’s rolling seas on the hunt for southern rock lobster.

What’s it like on a bad day? “It’s shithouse,” says Slim. “It takes the fun out of it that’s for sure, and that’s why I try not to fish too many bad days. With the catch rates being quite reasonable, we don’t have to fish as many bad days like we used to.”

Moments later and Slim’s deckhand (and son-in-law) Clint Slape – a carpenter from Millicent – arrives. It’s his second season on the water. The sea still shakes his stomach. But on the morning we meet, the air is cool and still and it’s into this stillness that the pair launches the tinnie from the Beachport boat ramp and ferry out to board the 13.5-metre fishing boat anchored in the protected waters of Rivoli Bay.

The rising sun starts to burn a deep red on the horizon as Slim motors up the coast, rounding Beachport’s commanding headland and Cape Martin Lighthouse, heading out into the rolling swell.

There’s an anticipation of what the day will bring. Out at sea, Slim’s 70 cray pots are sitting on the bottom of the ocean, hopefully full of legal-sized crayfish that have crawled in overnight, if they haven’t been poached by opportunistic octopuses.

Each day, Slim and Clint cover 80 kilometres of the spectacular coast from Beachport to Nora Creina and almost to Robe. The pots are set in deep water at this time of the season but in the warmer weather, Slim will drop them closer to the reefs and jagged rocky ledges of the rugged coast.

“There are only a few of us who are game to fish so close in and around the reefs. There’s definitely more risk involved (with the boat), but you never take things for granted and you have to be very careful,” says Slim.

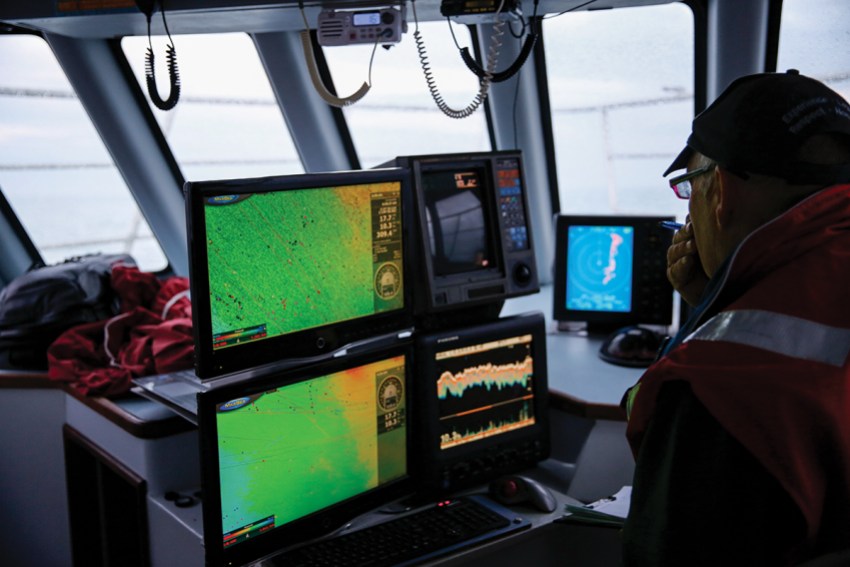

While the boat heaves and rolls, Slim switches on a portable butane burner to boil the kettle. The skipper displays a superhuman immunity to motion sickness as he buries his focus into his screens and paperwork. Working on the ocean is natural.

“I love it. It’s always been about the thrill of the catch as well as the serenity; it’s a stunning coastline and just a nice place to be on a nice day. Every day is a little different but it’s a good lifestyle,” says Slim.

Known to most only by his nickname – acquired as a young man when he lost a few spare kilos – Slim is a carpenter who happened into the fishing business by chance. Nearly 30 years ago, he was building a kitchen for an Italian fisherman who wanted to retire and lease out his crayfishing licence.

“Even back then, professional licences were as rare as rocking horse shit. Most of them have been handed down through the families, so I’m a bit of a rare case,” he says.

Out on the deck, Clint uses a guillotine to dice up salmon pieces, ready to re-stock bait in the pots. Clint grew up on a farm near Millicent and, other than a bit of amateur fishing, the experience has been completely new to him.

“Slim’s taught me everything I know. He’s quite patient and just a genuine, happy guy to work with. He’s also a well-regarded member of the community,” says Clint.

Seasickness has been the biggest challenge for Clint. The smell of salmon guts certainly doesn’t help, but he is persevering. Most people can become acclimated to the sea with time.

“When you have a good day on the water, you can’t beat it, but when it’s rough and you’re sick all day, it’s a long bloody day. I’ve talked to other deckies who tell me it’s a matter of time; one day it’ll stop,” he says.

“In December and January, we’ll fish close in along the beaches where it’s quite pretty and you see more dolphins and a few seals. Those days don’t feel like work at all.”

Most of the heavy lifting falls to the deckhand who hooks the buoy line with a gaff before winching the pot up to the boat. Once the pot is checked for crays and restocked with bait, the skipper positions the boat to drop the pot as deep as 100 metres, accounting for the drift of the tide.

“Once the day starts to tick along, you’ve got the radio going and you just do your thing. It is exciting when the catch is good,” says Clint.

Over the course of the day, they pull in some pots full of large, red crustaceans noisily flapping their muscular tails. Other pots come up empty, some contain undersized crays or spawning females that must be thrown back, but as the day wears on, there are plenty of keepers.

And not only does the weather hold, but it pans out to be a good haul of 170 crayfish – about 130 kilograms. To make things sweeter, Slim gets a call to say that prices have been increased to $60 per kilogram, the most it’s been this season by a good margin.

Slim sells his catch to the Limestone Coast Fishermen’s Co-operative (LCFC) which has live holding facilities in Beachport and Port MacDonnell. From there, the LCFC exports southern rock lobster around the world. In its fourth season, the co-op was founded by local fishing families to secure a viable future for them and the coastal towns and communities in which they live and operate from.

Slim is a board director and member of the LCFC which divides profits among members at the end of the season. Slim explains: “The fishermen could see everything changing in the industry as corporations started to come in and buy up licences and processors, so we decided it was time to respond in a proactive way and take some control.

“We’re trying to help the small towns to survive by keeping the money within our regions. It’s changed our mindset because we now know exactly what’s happening within the industry and the marketplace. We had been left in the dark over the years.”

The co-op has helped fishermen like Slim to steer through troubled waters and achieve a sense of ownership. The market bottomed out in recent years with Covid and then China trade issues, but demand throughout Asia remains strong, with exports landing in ports such as Hong Kong, Vietnam and Taiwan.

Visitors to Beachport can buy crayfish direct from the co-op’s shopfront, called The Lobster Pot. Christmas is traditionally their busiest time of year.

“It has been tough times, but we’ve survived,” says Slim. “From a co-op member’s point of view, we have greater understanding and information given to us about the market and the way things are running full stop.”

The Limestone Coast lies within the Southern Zone fishery which has been under a quota management system since the early 1990s. Slim says there was a period, well over a decade ago, when the quota was higher but fishermen were catching fewer crayfish. In response, the quota was tightened to support the health of the fishery and catch rates have bounced back. Slim believes the fishery is in a healthy position.

“The sustainability is good, and the quota is at a very sensible and sustainable level,” says Slim. The quota across the fishery this season is 1320 tonnes, of which Slim is licensed to catch 7.8 tonnes.

After a full day’s fishing, Slim arrives back in Beachport where the crayfish are weighed at a Fisheries depot and then the payload is dropped off to the co-op. Clint and Slim prepare bait for the next day. A beer goes down well after 10 hours of pulling cray pots. Slim then fillets some fish for a Friday night ritual where he cooks dinner for his old Italian mate who started him on this journey 28 years ago.

“We’ll drink some red wine, cook some seafood and have a chat. It’s a nice ritual,” says Slim. “He loves the company and it’s something he really looks forward to on a Friday night. I started doing it years ago and just stuck with it.”

It seems that most people look out for each other in Beachport. It’s common to see the deckhands sharing a beer in the front bar of the pub at the end of the week. Clint says: “We’re all mates out there together and you want to see each other get home safe. The fishermen are quite passionate, and for a lot of them it’s all they’ve ever known.”

Slim agrees: “It is a great place to live. Little Beachport is a hidden secret.”

This article first appeared in the December 2022 issue of SALIFE magazine.