There have been many significant moments in James Muecke’s life and they’ve all led him to one of the most prestigious honours to be bestowed upon an Australian.

James Muecke: Clear vision

When James Muecke’s name was called by Prime Minister Scott Morrison, signalling the beginning of his 12 months as Australian of the Year, the Adelaide ophthalmologist was truly stunned.

“I didn’t know beforehand, although people did ask me if that was the case,” James says.

When SALIFE meets with James, it’s not even a week since the announcement and his voice is hoarse from what has seemed like one long, endless day. The moment he finished on stage, he was thrust in front of cameras, interviewers and microphones, and bombarded with questions. “Your adrenaline is going and it’s insane. It’s really only starting to ease off now.”

The night prior to the announcement, James had a mere two hours of sleep, then, bedtime after the ceremony was 2.30am, followed by a 4.30am wake-up call.

“I’ve been trying to get back to normality but there’s been a constant barrage — I think I’ve had about 500 texts, 500 emails and at least 100 Facebook messages. I’ve got patients from all over the country wanting to come and see me, so I’ve been trying to field those.”

Adrenalin, coffee and Panadol are the only things getting James through the madness.

The night has cast a spotlight on James, but his success has been a slow burn over years filled with humanitarian work.

James can’t remember a time that he didn’t want to become a doctor — he would watch television show Emergency while he was a child living in the United States with a father who worked for the Australian embassy in Washington. “It was about paramedics and it was my favourite show; maybe that inspired me.”

When he was asked to contribute a significant memento to an exhibition in the National Museum in Canberra, James chose a Hawaiian statue he’d begged his parents to buy for him when he was 11 years old. “On the back, it talks about how the god helps children get through difficult studies. I knew I wanted to do medicine so I pleaded with them to buy it. It sat on my bookshelf and looked over me through medical school and beyond. It’s fun to think it might have had some sort of influence.”

Years later, James’s son Tom didn’t qualify for medicine the first time around so James dug out the souvenir, and he passed. “I asked Tom after the exhibition opening if he ever thought about it or looked at it and he said it actually made him believe in himself. I think there’s something to placing your faith somewhere, although I usually recommend placing one’s faith in oneself and one’s abilities.”

When James failed to get into the University of Sydney by one mark, a series of sliding door moments in his life began. Instead, he returned to Adelaide for medical school. “For six years, I worked really hard. I probably could have worked a lot less hard and I probably missed out on a few things as a result, but it’s just my nature to put 100 per cent into everything.”

After medical school, he came to another fork in the road. James had begun designing furniture while at university and was seriously considering it as a career, desiring a change. By the end of his internship, he says he’d become a little jaded with medicine. “The internship was full-on; we used to have 34-hour shifts. By the end of that, I just needed a break. I was really considering dropping out of medicine to design and build furniture. A lot of what I was exposed to was chronic disease and, often, self-inflicted from smoking and diabetes, things like that. You were just alleviating people’s suffering, which was important, of course, but I was tired of studying and tired of not being able to cure people. If I can’t fix or reverse something, it frustrates me.”

James was drawn to ophthalmology and micro-surgery. He’d become interested in model-making and was crafting clocks, which he sold to JamFactory, and could use his hands in a similar way with the specialised profession.

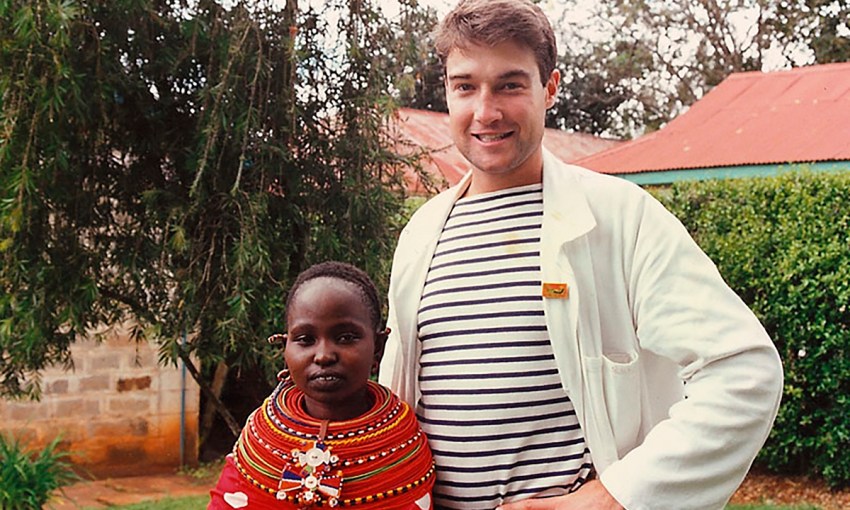

Taking a year off from study to work in a little hospital in the Kenyan mountains rekindled his passion for medicine. “It was really refreshing because most of the patients had infectious diseases or trauma, but they got better. It was fantastic to do rounds in the morning and as you cast your glance over the ward, there would be patients bolt upright in bed with big smiles on their faces and you knew they were better.”

Not every day was quite so rewarding though. James contracted malaria twice, amoebic dysentery once and left the country with just the dirty laundry in the bottom of his hamper, having been violently robbed five times throughout the year.

Perhaps the most daunting experience came when James and a travelling companion were traversing a civil war-plagued southern Uganda. They arrived at a village that had been occupied by rebel soldiers. “This group surrounded us; they were drunk, they were filthy and they were really menacing.”

Their backpacks were torn apart and the pair were accused of spying after binoculars were found. “They took us to a ramshackle hut on the edge of the village. We were convinced they were going to do away with us.”

The pair escaped into the national park behind the village and had the impossible decision to either continue into a wild landscape full of lions and hyenas, or turn back and face possible murder. They turned back and caught a lift with a car leaving the village. However, as soon as they got in, it turned back towards the village. “They said they were getting petrol but they disappeared for about half an hour or an hour and when they came back, they’d been drinking.” As the car pulled away, their captors came out of a bar and all the men pointed and laughed at the foreigners; the driver was in cahoots with the rebel soldiers.

It was a tense drive, to say the least. James remembers the driver stopping a few times to put water in the radiator and thinking each time he was about to be shot.

For years after, he’d wake up with nightmares and in retrospect, he believes it could have been PTSD.

James arrived home, a little worse for wear after his last bout of malaria, and soon met his now-wife, Mena, who remembers him being quite gaunt.

They were brought together by their shared interest in design and architecture and James was clearly smitten from the start. “She was talking about Glendi, the Greek festival and I was dropping hints that I’d love to go. Eventually, she invited me and we had this fabulous day together. I remember saying goodbye and jumping in the air and clicking my heels together.”

James describes Mena as his best friend — they live together, work together at the charity James founded, Sight for All, and they travel well together.

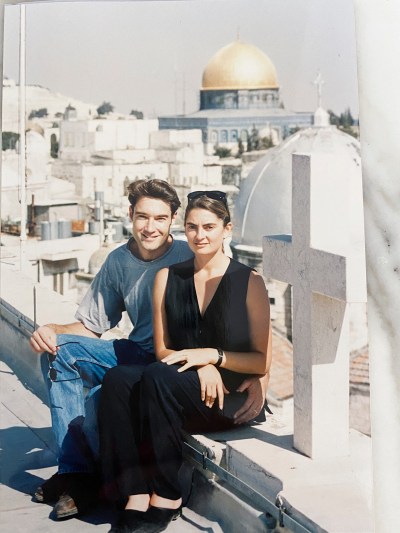

Two years after marrying, they moved to Jerusalem for a year and, like Africa, it was exciting, turbulent and life-changing.

While James was working at St John’s Eye Hospital, Mena found work with architects. “The summers are extreme, so I started taking an earlier bus to work,” Mena says. “I remember I got to work and the 7.15 bus I normally caught was blown up.”

James would visit the west bank in the Gaza strip on outreach trips to see patients in refugee camps and villages. The hospital van would be stoned regularly because the Palestinians thought they were Israeli.

“One of the days coming back from the clinic, they were burning Israeli flags and tyres,” James says. “We were in the hospital van and before we knew it, we were surrounded by this mass of people with murder in their eyes, rocking the van and shouting.”

Luckily, the Palestinian driver and nurse managed to placate the rioters. “They backed off and it was like the waves parting for Moses and we went on and were able to get back to safety.”

Nevertheless, the couple fell in love with Jerusalem and remember it as a magical time filled with feasts and weddings, both Jewish and Muslim, and Christmas celebrations in Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity.

When James became involved in teaching his skills to doctors in Myanmar, he realised they were sorely lacking in exposure to medical expertise. He set up a program to help his colleagues learn more about ophthalmology and Sight for All was born. “We weren’t just doing surgeries and leaving, we were actually teaching colleagues and leaving those skills behind.”

The charity brought doctors to Australia to train for 12 months and sent them back home to teach others and get to work. They trained a children’s eye specialist, who became the first paediatric ophthalmologist in the country. He’s treating nearly 30,000 children each year, along with his group of trainees.

After two decades in the design industry, Mena decided to join the charity as it was becoming harder for her to juggle her job and the couple’s two boys, Nick and Tom. “I probably naively thought it would be fun to run the events,” Mena says.

In the charity’s first decade, it raised $1 million, with a lot of dedication from Mena, in the form of events such as Sculpture for Sight and One Night for Sight.

“I’ve really enjoyed it. The events are still aesthetic, so I get that fix but I like the fact that I’m doing something more meaningful. Design is amazing, but when you’re accompanying your husband to these really poor countries and seeing that actually, just getting a meal a day or getting an eyedrop is the biggest thing of the day, it puts it into perspective a bit.”

James says Mena has been a great sounding board and problem-solver. “It’s been a fabulous thing for our relationship, working together to solve a significant social problem,” he says.

“I’ve been quite consumed by my practice and Sight for All — she’s really the one that has guided the boys through their schooling and any issues. She’s incredibly wise and incredibly supportive.”

Mena has been by James’s side through the process of setting up his practice, all the humanitarian work and every side project along the way, including a foray into music, which culminated in a record company and two EPs on iTunes. “I bought myself a keyboard, synthesiser and musical production software and started creating music. I’m an early morning waker so I’d make music at about 6am before the day’s work and Mena would hear the sounds drifting through the house.”

Mena will be there throughout the year as James casts his new spotlight over the issues that are foremost in his mind. In January, James had been doing a lot of reading and thinking about the link between blindness, type two diabetes and sugar consumption.

He used his platform on the Australian of the Year stage to wage a war on sugar, though he says he’s not trying to be evangelical, but wants to champion the benefits of moderation. “I’ve detoxed from sugar myself and it’s actually quite an unpleasant experience.”

James has gone from eating a pack of cream biscuits every day and ice cream every night, to more mindfully enjoying sweets.

He wants to champion awareness about type two diabetes and show people just how preventable it is. He’d like a sugar levy and less accessibility — no more chocolate advertisements blaring at us in countless forms throughout the day. Perhaps even a traffic light system to make sugar consumption plain and simple.

Even with winning Australian of the Year and clocking up the miles for work trips and all the other things that keep James busy, Mena says she and the boys always feel they come first, and they couldn’t be happier to be by his side.

“James’s enthusiasm for all his projects, be them creative or humanitarian, is highly contagious and we love going on the ride with him.”

The award and the doors it has opened couldn’t have come at a better time for James, who has ceased his surgical work due to a neurological condition affecting the muscles in his hand. “Rather than letting it get me down, I’m embracing the change. I’ve had lots of transition in my life and this is just another one.”

This story first appeared in the March 2020 issue of SALIFE magazine.