The best-known oval curator from Adelaide to India, Les Burdett has earned the respect and admiration of cricket fans worldwide. SALIFE finds out if the grass is greener 10 years into retirement.

Les Burdett: The Pitch Whisperer

“What have I done?” Les Burdett approached the hallowed Adelaide Oval gates in a familiar ritual he’d carried out most days of his adult life. The Moreton Bay figs, the scoreboard, the hill and the cathedral in the distance; everything was as it should be. But on this occasion, something was off.

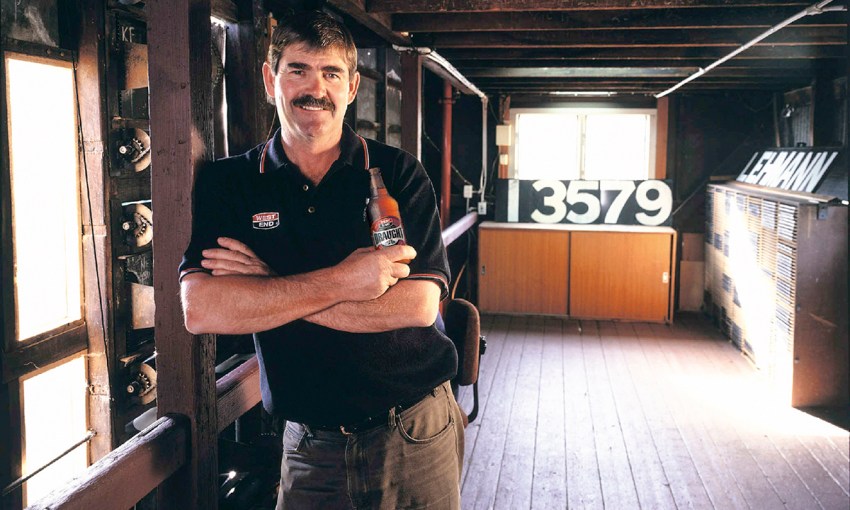

He scanned his member’s ticket at the gate and continued into the ground. It was the first Test match after his retirement from the curator’s job in 2010 and, for the first time in 41 years, Les was a spectator. “I thought, ‘No, I’ve made a mistake … I’ve let all this go’,” remembers Les, who endured all five days of that Test like a sportsman forced to watch his team from the grandstand.

It is now 10 years since the man dubbed “the pitch whisperer” called stumps on his career at the oval. As is often the case with sporting greats, the transition to retirement is not easy at first. “It took me six months to get over it, but I look back now and it was definitely the right decision and time to hand the baton over, too,” says Les.

As an honorary life member of the South Australian Cricket Association, Les’ name adorns the same honour board as those of Sir Donald Bradman and Ian Chappell. He’s garnered accolades such as the Australian Sports Medal, the Australian Centenary Medal and the Medal of the Order of Australia. Not bad for a groundskeeper.

“The pitch doctor” has been called upon to advise on the health of pitches around the world, and continues to lend his expertise to sporting grounds across the country, from suburban cricket clubs to the MCG.

It’s only in the game of cricket that a curator could gain such renown. “Sir Donald Bradman once said that no sporting surface has more bearing on the result of a game than a Test cricket pitch,” says Les, while sitting in his lounge room with a view to his well-kept garden and front lawn at West Beach.

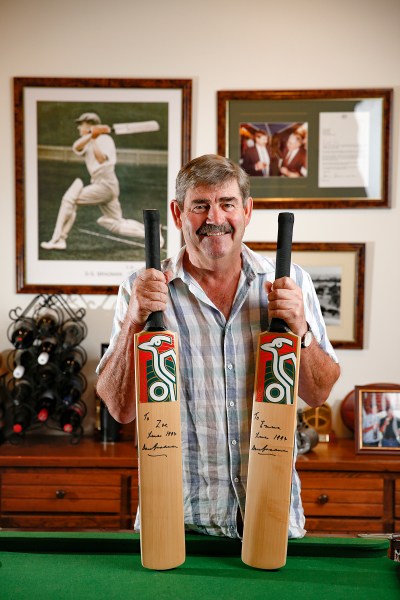

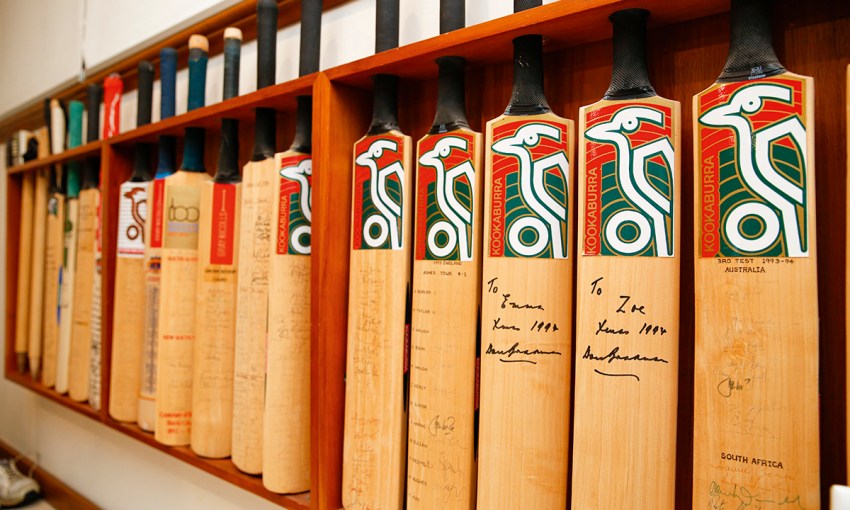

Today, Les and his wife Jane live in the family home where they raised their daughters Zoe and Emma. The house contains some lovingly-curated pieces of cricketing history: a dining table made of timber salvaged from the Bradman Room ceiling, a length of picket boundary fence, and a potted Moreton Bay fig propagated from a giant cousin. Planted in his back lawn are small sections of Adelaide Oval turf.

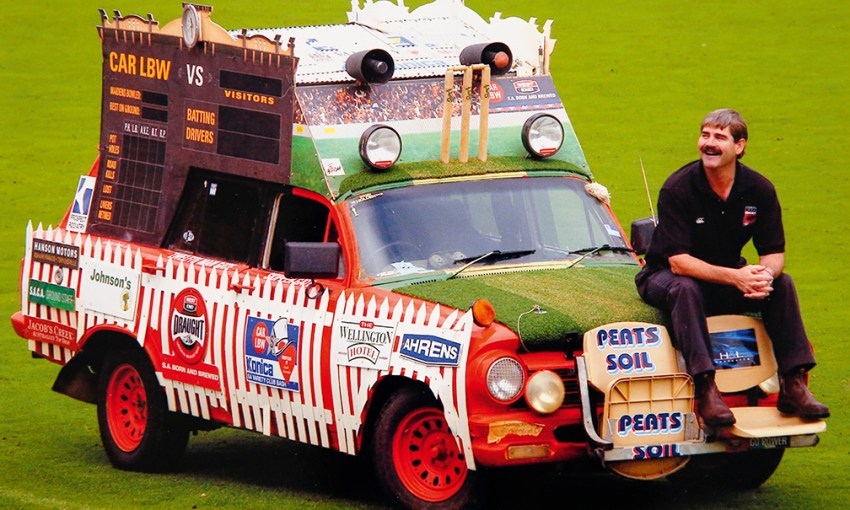

Not one to sit idly in retirement, Les runs a sports ground consultancy business, is Pitch Advisor to Cricket Australia, volunteers as an ambassador for Variety Children’s Charity, babysits his grandson, Max Les Kelly, and enjoys walking the local beach. This year would have been his 20th straight Variety Bash, had it not been cancelled due to COVID-19.

“I feel sorry for so many high-profile sportspeople that haven’t got something to turn to after sport; they can’t all be coaches,” he says. Although Les enjoys a beer and is famous for starring in a West End commercial, as well as a media stunt when he and Tony Modra remarked the Victorian state border, he’s in good health as he approaches his 70th birthday in January.

Health is something Les doesn’t take for granted. What he didn’t reveal publicly when he retired in 2010 was that his decision was driven by a cancer scare. A prostate biopsy had come back all clear, but Les saw it as a red flag and decided it was time to call the end of his innings at the oval. Two years later, after a tour of Italy with Jane, more tests indicated things had progressed and he required surgery to have his prostate removed.

“That was an emotional time and the toughest part was telling the girls. I tried to stay strong through the whole thing, thinking it was going to be all good, but you never know,” says Les, who is currently in the clear.

Since his surgery, Les has met with dozens of other men to talk them through the same experience. “Someone did that for me, and it was so helpful to know what to expect. There are many aspects of it to understand and come to terms with,” he says.

Les was raised one of seven boys at Beulah Park. “The brothers have stuck together, we’re very close; always have been,” he says. Their father Len was a builder who would sometimes pull Les out of school to help him finish a project. As a youngster, Les sold newspapers at the Kensington Hotel and then, at the age of 13, got his first taste of working at a sporting ground — not for cricket, but baseball.

On a school night, his job was to put up the homerun fence for baseball games at Norwood Oval. “They had this old Model T Ford that you’d have to crank start. I learnt to drive on Norwood Oval — towing the signs, each about three-metres long, right across the ground,” he says. “I’d come back later, watch the end of the game and take it all down again. I’d walk up Norwood Parade, have a pie floater by the town hall and get to bed about one o’clock. Mum would wake me up for school the next morning.”

In 1969, Les scored a job as the understudy of legendary Adelaide Oval curator Arthur Lance. From the moment he started work, two weeks before man walked on the moon, Les began learning the art of curating cricket pitches and absorbing knowledge from Arthur. Les wasn’t pulling weeds, he was learning the top job and he loved it. Les was also playing football at the time, but that all paused when he was conscripted for national service in 1971.

Les, aged 19, was training with the military engineers in Queensland in preparation for Vietnam, when Australia began pulling troops out of the war. “I was in booby traps and demolitions. I’m pretty impatient, so I probably would have blown myself up,” he says.

Les was allowed to pack his bags and leave the army, but stayed on to complete his full 18-month national service commitment. “I decided to see it out and I’m glad I did. The army made me a better person, and a better team player, no doubt about it. The army taught me respect and that you’re only as good as the bloke alongside you,” he says.

Upon returning to his job at Adelaide Oval, Les studied ornamental horticulture while continuing his tutelage under Arthur. “He was like a second dad to me,” says Les, who was 27 when his mentor suffered a heart attack and was forced to retire, leaving Les to take over. He officially become curator in 1979.

“I was the second-youngest on the staff of about 14 men. I had to very quickly earn respect to have these guys walking behind me,” he says. Les thrived in the job with his work ethic and mindset. It was no walk in the park — preparing the oval for events such as an international Test match was a mammoth undertaking.

“It was crazy. We’d be there very late at night, most nights. I’d start with the cricket pitch, to the outfield, to the marquees out the back, to the buildings and cleaning, it was a quite a big portfolio to cover. The job wasn’t done until it was all finished. Zoe and Emma would often say to Jane ‘When’s Dad coming home?’”

“Running Adelaide Oval is like setting up your house for a 21st birthday party and looking at the mess the next day. You want to present your house as pristine every time, then you have to watch everyone trash it. Then you come back in and fix it again.”

In between the demanding work, there were moments of bliss. “Late at night when I was finishing up, I’d sit and listen to the cathedral bells and the seagulls with nobody else there; it was just beautiful. I still have a love affair with the oval. It was the best office in the world,” says Les.

“It has always been the most majestic cricket ground in the world, as far as I’m concerned.”

Les did fulfil a dream by winning a football premiership on Adelaide Oval in his last ever season, captaining the Adelaide Teachers College A1 reserves side.

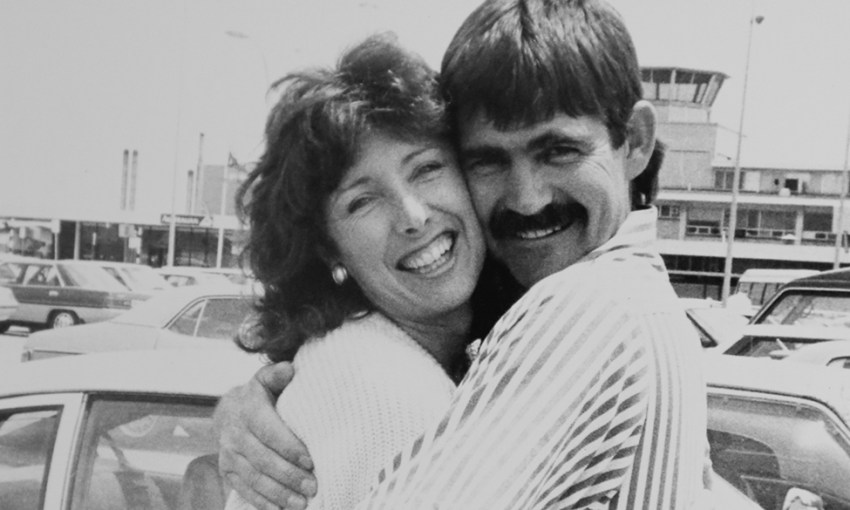

Les was 24 when he met his wife Jane, who is now a lecturer in human resource management at UniSA’s Business School. An academic seems an odd match for a “turfy”, but she was a cricket tragic who fell in love with Adelaide Oval long before the couple even met.

“I grew up in Port Pirie and Dad would drive us down to watch Sheffield Shield cricket,” Jane says. “To sit at Adelaide Oval under the Moreton Bays, we just thought it was the best.” After meeting at a mutual friend’s party, Les’ first phone call to Jane was dialled from a telephone box attached to the Adelaide Oval scoreboard.

“When I found out Les worked at Adelaide Oval, there were two things,” Jane says. “I thought that’s great; he might introduce me to Greg Chappell — my favourite player — and he’ll also get tickets to the cricket.”

Les is known for his hospitality, which he says comes from his mother, Margaret, who died after an accident on a camping trip. “I was 19 when my mum passed away. Remembrance Day means a lot to me because it was the day mum was buried. It’s also special having done the national service commitment,” Les says.

“Every morning when my six brothers, Dad and I were all living at home, Mum would feed everybody. On weekends she’d do a roast and most of us would bring a mate.” Les continues that tradition today by cooking a Sunday roast when he gets

the opportunity.

The most satisfying part of Les’ career is the friendships he’s made along the way. From the late David Hookes to Darren Lehmann, and players such as Adam Gilchrist, and the West Indies’ paceman Joel Garner.

Today he continues a tradition of toasting to the first ball of the oval’s first test match of the summer — a custom that originally started with Les, David Hookes and cricket executive, the late Barry Gibbs.

“There’s now a group of about 30 of us that meet at the oval as the first ball is being bowled. We have a beer and toast to the success of the team, to Australia and all absent friends,” Les says.

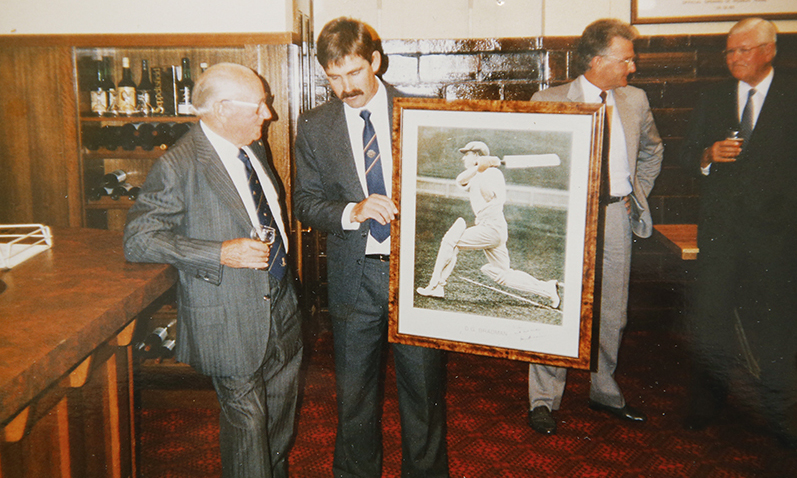

Throughout his career, the curator would join players for a post-match beer to seek constructive criticism on the pitch condition. On a particularly memorable occasion, after Dennis Lillee’s last Test match at Adelaide Oval in 1984, Les was called up to the rooms where Lillee was waiting to pour him a rum and coke. As they shared a drink overlooking the oval, Lillee said (as Les remembers it), “Whatever you do, don’t compromise what you’ve got out there. That’s an honest Test cricket pitch and that’s the way it should be. Wickets don’t come easy, but you’ve got to work for it.”

Some grounds have been known, infamously, to fix a pitch to favour the home team. Les frowns upon the notion of curating a pitch to suit one side. “You could contrive a pitch easily if you wanted to, but the art is to produce one that is true to the game and that’s the bit that I love.”

Despite the accolades and sporting fame, the curator’s success boils down to his determination to uphold the reputation of Adelaide Oval, his family and his staff — something he has passed on to current curator Damian Hough.

“I like to think I was good to Adelaide Oval, but at the same time Adelaide Oval was so good to me,” says Les.

This story first appeared in the August 2020 issue of SALIFE magazine.