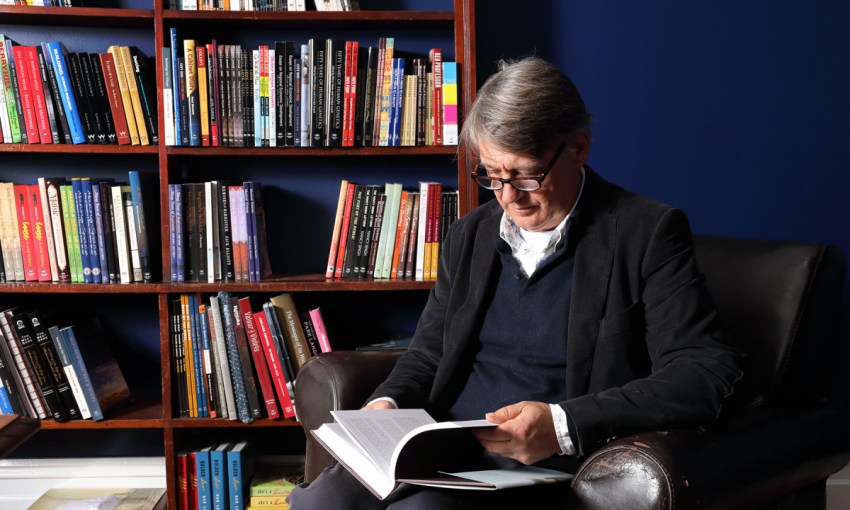

Michael Bollen, director of Adelaide-based independent book publisher Wakefield Press, likens himself to a wombat - always burrowing ahead. After more than 30 years in the publishing game, he still finds immense joy in being part of the industry.

“You can let yourself be told a story, at your own whim and pleasure”

Where did you grow up?

My earliest years were in Adelaide’s eastern suburbs (Leabrook). I’m growing up now in the inner west, where my home and work are a minute’s walk apart. I occasionally leave Rose Street, Mile End.

Can you paint a picture of your childhood?

I was born in June 1959, the year television came to Adelaide. I believe my grandparents gave our family a TV set to celebrate my arrival. Later, the cats used to battle for nesting rights on the warm television top, Soxy pushing off Tabitha, whose balance hadn’t been flash since her tail was removed (it got stuck in a door).

I can’t recall which dog, Suzie or Itsy-Bitsy, or maybe it was both, we waved off to (so my parents gently said) “a farm” after postman-biting incidents. Or was it the milkman? Less formidable was the small white replacement, poodle Hercules. Hercy slept under the Holden out the front, acquiring oil-spill grime.

My older sister, Jenny, and younger brother, Andrew, are close in age and we are all good friends. Archetypally, as youngsters we’d bicker among ourselves, but defend each other against others. Our mother died when we were teenagers. Only later, and probably not even now, did I appreciate how much ‘mothering’ my strong sister took on then.

For some early teenage years, we lived in our relatively sedate leafy-suburban house next to the legendary art and jazz entrepreneur and innovator Kym Bonython and his family. Their home was decked with modern art and sounds. I’d walk in to grab Tim Bonython (my age) for our hours of cricket in the park, and meet Count Basie or Barry Humphries sitting there, or someone like that. One vivid memory is we staid Bollens peering over the fence to watch Big Pretzel jump out of a cake at Kym’s fiftieth birthday party.

Dad was a lawyer, much later a judge: ‘”short-sentence Bollen, gave them and wrote them”, a lawyer once said. Mum had been a nurse, and was reading a lot of archaeology before she died of brain cancer in her mid-forties. She was always busy with the Asthma Foundation – her father Dr Cyril Piper founded it, I think – Meals on Wheels, tennis, running after us kids, helping her sister tend the many great aunts.

Some of the great aunts would arrive on Sundays for a barbecue. Dad would sweat over the chops as he charred them to buggery. I’d complain that I couldn’t watch World Championship Wrestling, while Andy continued quietly making his model planes or re-reading Shakespeare (he’s very smart). Later in the day, we’d toddle off to the paternal grandparents’ for afternoon tea, Grandma Kathleen, with her limpid blue eyes, tending the trolley with its layers of cakes, and allowing us – encouraging us! – to add sugar cubes to our Woodies lemonade (screw-top), and dunk our chocolate fingers biscuits. I still wanted to get outside, though.

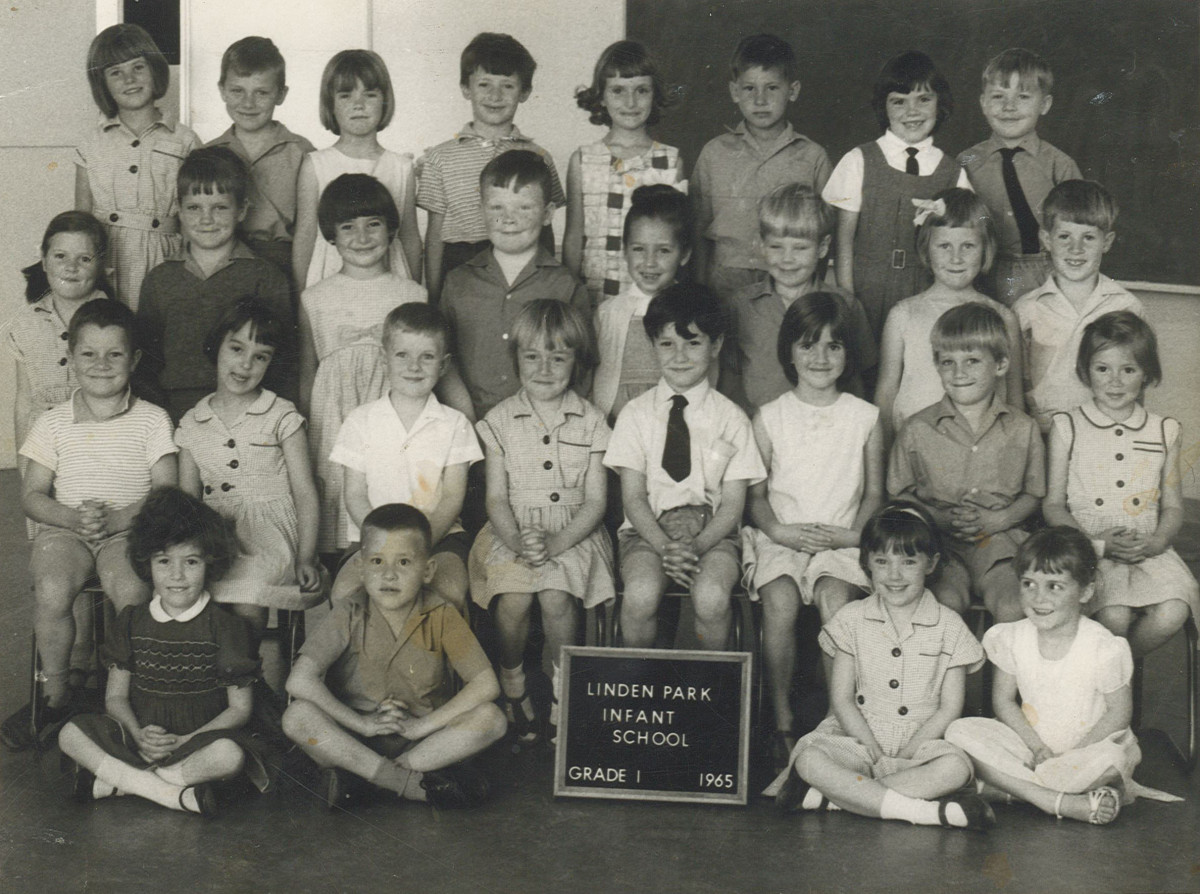

Tell us about your schooling.

For some reason I just don’t know, I was terrified of primary school early on. Well, it was so much cosier at home. If I pulled a sickie – which was often – Mum would wheel up the trolley with the television and a cream bun for me to watch in bed. Sorry, Mum! Must have been really tedious.

Later, I never found school work too hard, once I’d got the hang of whatever subject, and was reasonable at some sports and making friends. Indeed, in that fishpond, I developed rather too high an opinion of myself, I know.

Conversation I can really enjoy, but have never been good at sitting still, listening to monologues. So I found a lot of school hours tedious. I have the pleasure now, though, of publishing books by at least two of my former teachers, Don Loffler and John Roe, as well as sundry others who were around in those days.

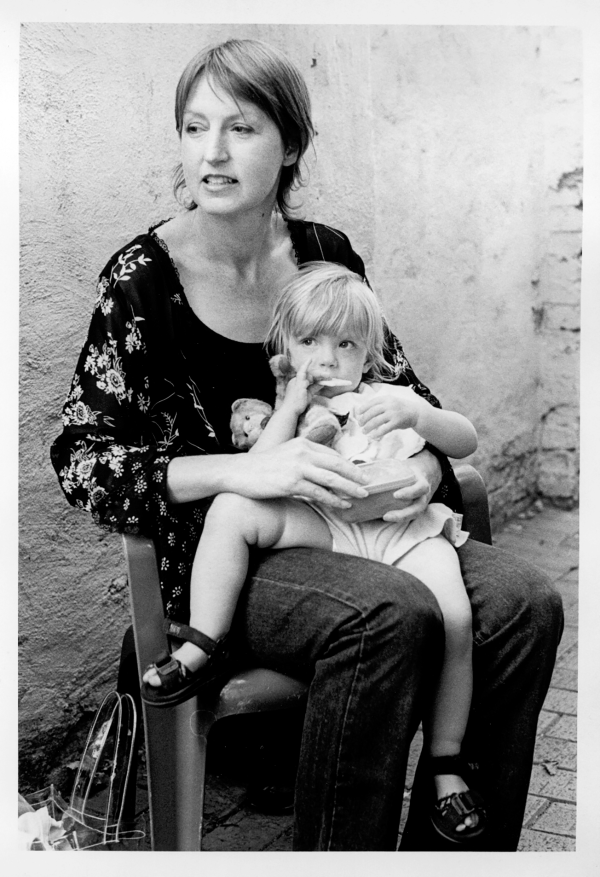

What’s your most vivid childhood memory?

One as a very young boy is being curled in my mother’s lap against her furry brown jumper, the kerosene heater warming the TV room, Mum patting my back, all smelling safe and sound.

What did you want to be when you grew up?

Usual sorts of ambitions: Test cricketer, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, famous author, world saviour.

Best and worst teenage memory?

Perhaps the same event. I won the Tennyson medal for English in my last year at school. It was a complete surprise: I was never the very top student in an English class. Anyway, I was happy and it gave me some social cachet for a bit. But it also gave me a swollen head, allied – as so often – with feelings of insecurity and a good dollop of laziness.

Straight after this, I left home to study in Canberra, home having become not so pleasant when my father remarried. I became that student who writes 100 variants of a first sentence, tears up them all as worthless, then heads to the uni bar for a solid binge drink and a smoke. I’ve never handled drink well, as many will testify. I finally completed a drawn-out and higgledy-piggledy BA degree in Adelaide, in my mid-twenties.

But things turn, as ever. If I’d had the academic career I thought may be mine (in god knows what) I wouldn’t be doing the work I do today. I love my work.

How did you get into publishing?

OK, so after I dropped out of university in Canberra, and did some hitchhiking and sleeping on people’s floors, feeling often lonely and lost, realising maybe Jack Kerouac’s wasn’t the life for me, although On the Road had promised so much, I got a job in the old Commonwealth Employment Service, and worked in various of its Adelaide offices.

I enjoyed my years there, and as a shy, somewhat stand-offish young person I learnt a lot, at the front counter and later as an employment officer, about how to communicate with people, how to ask questions and listen to answers, how to enjoy their many and various stories. I liked the feeling of helping people, jobseekers and employers alike. A quirky time was arbitrating a strike at a strawberry farm, where recently arrived “boat people” from Vietnam and Cambodia wanted better pay (proud to say they got it).

Among friends I made was a colleague named Michael Vanstone, a great wit and sharp as a tack. He left the CES to help set up the Adelaide Review, then becoming established as this city’s first free arts and parish-pump politics magazine. Meanwhile, I too left the CES, running off with my supervisor and eventually completing a tattered degree, learning a lot between drinks about cultural politics from luminaries like Noel King and Stephen Muecke.

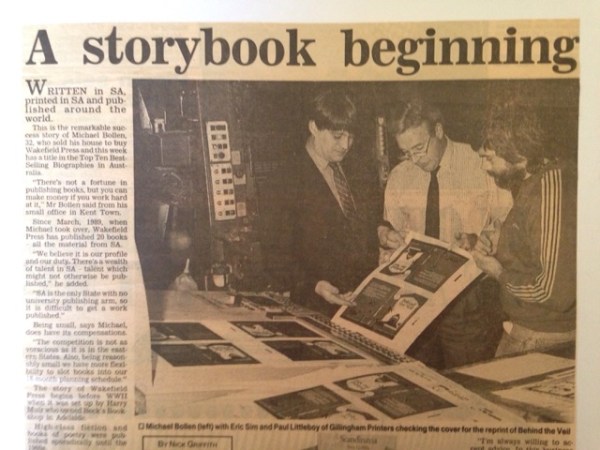

The relationship with my ex-supervisor ended sadly (mea culpa), and I took to my bed, in my cottage in the hills, for too long. At last, I harassed Michael Vanstone into giving me a job at the Review. They had just acquired the state government-owned Wakefield Press. Well, in fact they acquired the name, a second-hand accounts computer, an agency right to market the books already published by WP (which had been set up in the early 1980s as a sesquicentary – SA’s 150-year jubilee – venture), and the duty of seeing some forthcoming titles to completion.

I got the job of sales rep for the books, combined with ad-selling and proof-reading for the magazine, and writing the odd review (after tearing up many sheets with first lines on them). After just a couple of years, when Michael had left for Sydney to start a sister paper, and an eternal truth – “no money in books” – was dawning on the Review’s owners, they started to make noises about unloading Wakefield Press.

I was about to turn 30, really wanting to make something of my life, had learnt a lot and met many people in those short years, had returned to self(over?)-confidence mode. Also, the tenant in my hills’ cottage appeared to be normally in gaol or otherwise unable to pay the rent, meaning I was unable to pay the mortgage.

So, after some negotiation, and by memory for the sum of about $2500 (too much!) I became the owner of the Wakefield Press name, and the agency right. Don’t think I got the second-hand computer.

There was some “who is this guy, what does he know?” around town when I took over, and fair enough. It gave me an extra spur to work hard. Now here I am, 31 years later, now just a 30-odd percent owner, all the hassles of small business and creative endeavour, but with days full of books and good people.

Most pivotal moment in your life?

Taking over Wakefield Press was pivotal. It wound me up and set me going in a groove. It’s the biggest challenge too. Every day has its obstacles. I think, though, I’m like a wombat, forever trying to burrow forward no matter what’s in the way. It helps so much when people acknowledge that what we are doing at Wakefield is important, that our work of “proudly publishing from Adelaide to the world”, telling South Australian and Australian stories, really matters.

Family life – married? Kids?

Pivotal too was meeting my wife, Liz Nicholson, 20-odd years ago. It happened through work, of course. Liz is a graphic designer specialising in books. At the time she was working with partners in a small firm, DesignBite, they owned in Melbourne. A veteran book editor, Jane Arms, who taught me a lot about publishing in the early days, recommended DesignBite to Wakefield when we were looking to publish a series of overlooked Australian crime classics.

So Liz and I met, then met some more, and this followed that, and not too long later Liz moved to Adelaide to be with me, for which I am forever grateful.

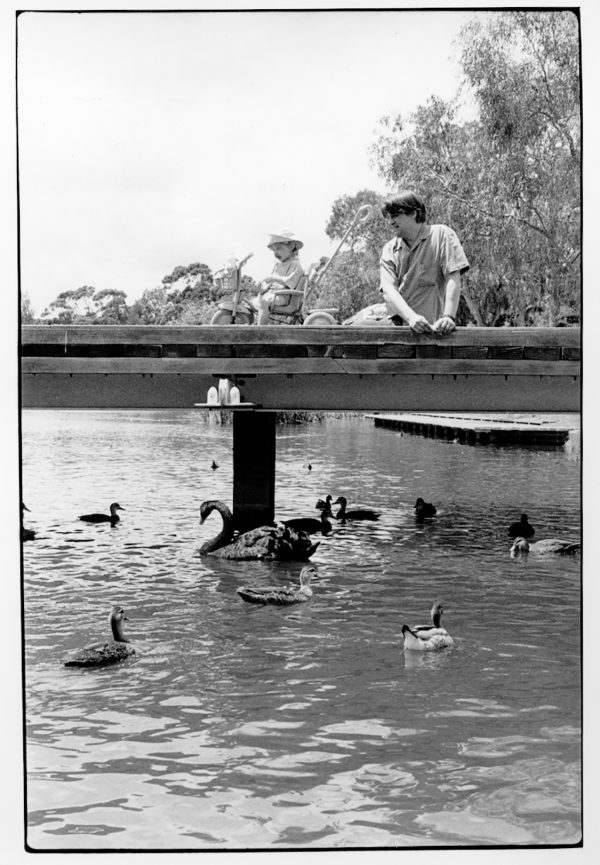

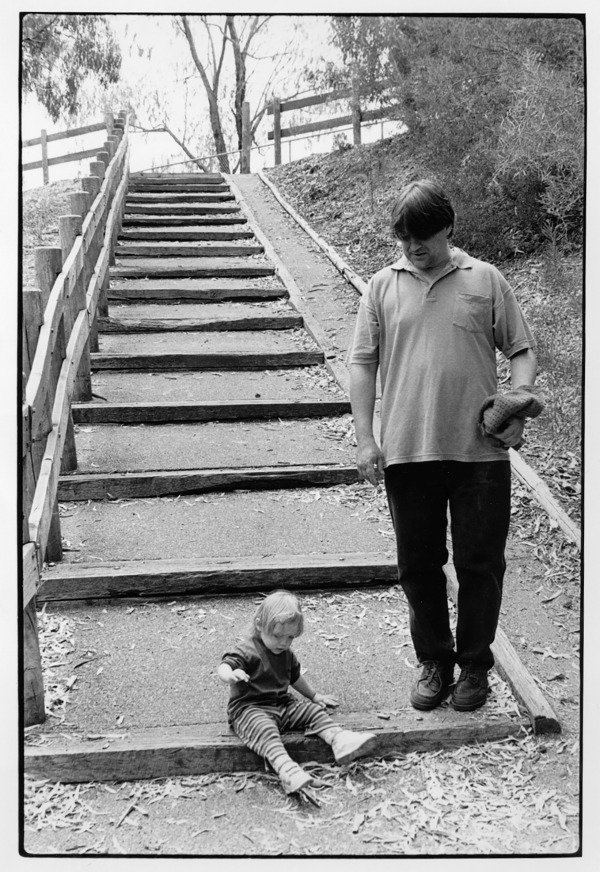

Without Liz, there would be no Emily Alice Anne, our daughter and only child. How can it be true that my baby is 20 next month? I thought I was too old, too broke, too irresponsible, all the bloke excuses, before Em appeared. We have a lot of fun together.

What brings you joy?

Walking the park lands, talking nonsense with my brother Andy and daughter Em, brings me joy. We shoot the breeze, laugh out loud. That feels “congruent”, like we’re in the right place and bits fit together. Similarly, I feel joy at work when “the machine” with its many functions and human interactions – editing, design, typesetting, marketing, sales, dispatch, invoicing – seems to be running smoothly.

Honestly, I feel a frisson of joy every morning when I walk out the front door into fresh air. That can soon dissipate with the day’s complications, but I’m fortunate, I think, never to have lost a sense of excitement with each new day (well, most new days).

Privately I find joy in reading, getting lost in a book. Music, art, Ashes test victories, films, our cats, Jacinda Ardern, compassionate politics – these bring me joy at moments. But with a book you can put it down, walk around a while, and come back to it without missing anything. You can let yourself be told a story, at your own whim and pleasure.

Who inspires you and why?

“Surround yourself with people who are cleverer than you are,” some business tycoon once advised. Our authors inspire me, as do my work colleagues and freelancers with their many skills.

Most of all, I think the aforementioned Liz Nicholson, my wife and powerhouse designer who has contributed so much to Wakefield Press, inspires me. Liz suffers serious chronic illnesses. But I know no stronger person. She is so damn good at her work, so quick and creative, so passionate about creating good books. And a great mum besides (rather more organised than I am, too. That helps.).

My South Australian Life is a first-person series, published each Sunday. Read our previous profiles here.