Resting beneath the waves of the Southern Ocean for more than a century, the sunken remains of South Australia’s maritime history have held a lifelong fascination for one young diver.

The Shipwreck Hunter

As the Edith Haviland pitched and yawed in stormy seas on a cold June morning in 1887, standing at the helm Captain J. Roddy would have been no doubt relieved to sight the guiding light of the Cape Banks lighthouse, far off in the distance on the south-east coastline.

For somewhere in the deep waters below the 264-tonne brig, laden with cargo, lay the ghosts of the Admella shipwreck.

Long after her ill-fated voyage in 1859, the tragic tale of the Admella, in which 89 people died in horrifying circumstances, had struck fear into the hearts of every seafarer that traversed the notorious south-east coastline.

Little did the crew of the Edith Haviland know, they were about to suffer a similar fate.

Around 2am, the brig struck a hidden reef and capsized in the rough pounding swells, her quarters filling with sea water as Captain Roddy gave the call for the crew to abandon ship.

Desperately, Captain Roddy tried to save his family, but his wife and three young daughters were dragged from his arms and drowned, along with a crew member who slipped beneath the pounding waves, as his exhausted shipmates watched on, unable to save him from his fate.

More than 130 years on, it’s a Friday morning at Carpenters Rocks and the sea is deceptively calm as a lone diver walks down the beach towards the rusting hulk of the Pisces Star — one of the Limestone Coast’s most photographed shipwrecks.

Mount Gambier’s Carl von Stanke was merely months old when the 60-foot sailing boat ran aground on the beach in 1997 — an untimely end to an elderly Victorian man’s dreams to sail into retirement.

But he knows the story by heart, as he knows many stories and statistics behind the roughly 800 wrecks scattered along the South Australian coast.

Nicknamed “the shipwreck hunter” for his ability to track down the region’s lost wrecks, the 21-year-old is uncovering the dark side of South Australia’s maritime history. Today, the long-forgotten wreck of the Edith Haviland is his quarry.

Zipping up his wetsuit and squinting in the bright January sun, Carl points at a spot on the horizon.

“That is where I reckon I’ll find the Edith Haviland.”

Taking into account his search time is confined to a brief window over summer holidays, Carl’s track record is nothing short of prolific. Over the past three years, sometimes with friends and sometimes alone, he’s discovered the historic wrecks of the Iron Age, the Lotus and the Flying Cloud, which all sank in the late 19th century.

When asked why he devotes his holidays to solving the riddle of lost ships, Carl smiles. “Because it’s a challenge,” he says. “Most of the world has been explored so it’s good to explore the things that haven’t been found yet.”

When Carl locates a wreck, the first person to hear about it is his dad Gary, a man who gets as excited about maritime history as his son.

As a young boy, Gary recalls, Carl was either in the water, combing beaches for new discoveries or in the library, eagerly scouring old papers and historical records for details of shipwrecks.

By his early teens, research had turned into action, with Carl joining Flinders University researchers to rediscover the wreck of the Hawthorn, which sank off the coast of Carpenters Rocks in 1949.

Many ask about his decision to target a specific wreck and Carl’s answer is simple: common sense. Of his decision to begin researching the Edith Haviland more than a year ago, he explains the 25 tonnes of scrap metal and wire she was carrying as cargo may make the wreck site easier to spot.

Like the relentless ebb and flow of the ocean, time dulls the ability to find accurate information on events that occurred more than a century ago.

Carl spends hours trawling the online newspaper archive Trove for old shipping reports, articles and snippets of information but sometimes he spreads the word of his search using the very contemporary world of Facebook.

Like Chinese whispers, shipwreck stories are passed on from generation to generation and artefacts from wrecks, now holding pride of place in garages and pool rooms, may help Carl narrow his search.

This time, however, requests for any local information come up short.

Although Carl has been able to freedive previous wrecks, for this search he calls in fellow diver, Whyalla’s Steve Saville and the pair head out in Steve’s 20-foot boat in a brief window of calm weather.

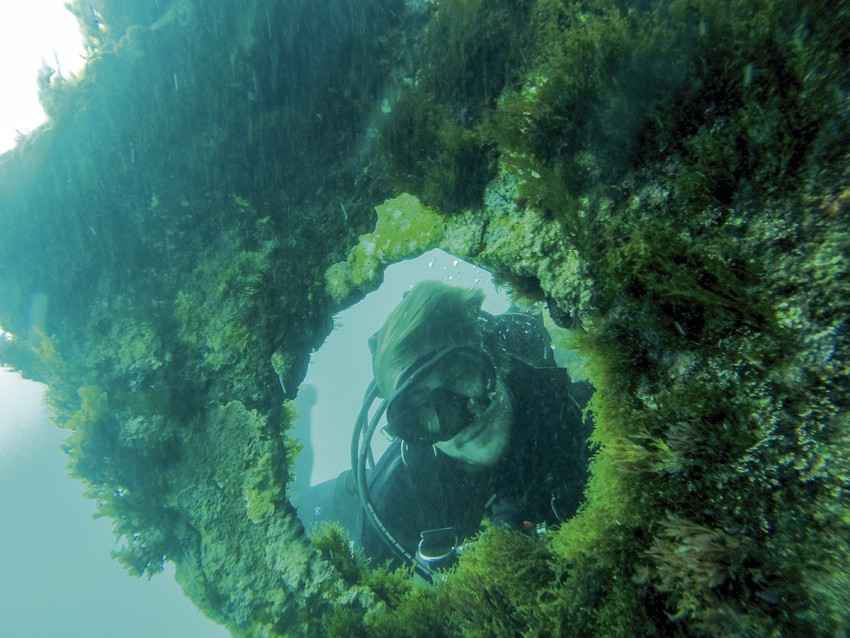

To the untrained eye, a shipwreck more than a century old is virtually unrecognisable. At the mercy of battering ocean currents and salt erosion, all that remains of once-sturdy structures are mere fragments of salt-encrusted planks and eroded metal, buried in sand and camouflaged by marine plants.

Searching for the Flying Cloud in 2016 with friend Santiago Neumann, the pair stumbled across the ship’s anchor chain, encrusted with seaweed, which would once have tethered the ship’s two main anchors. Surprisingly, the chain was still pulled taut.

The Edith Haviland signals a turning point of sorts for Carl. It’s the first time he is pursuing a wreck where there was loss of life.

Any wreck over the age of 75 years is deemed protected under South Australia’s Historic Shipwrecks Act, whether it has been located or not, however a wreck where human remains lie make a site of grim significance to souvenir hunters.

Protecting and managing the remains of South Australia’s estimated 800 shipwrecks is the job of the Department for Environment and Water’s State Heritage Unit, but it’s an enormous area to cover. With the assistance of local divers such as Carl, the state’s shipwreck sites can be located and documented to protect and preserve the wreck for the future.

For this summer, the secrets of the Edith Haviland will remain undisturbed.

Frustratingly, Carl believes he and Steve came to within around 100 metres of the wreck’s resting place and even found what they believe could be old timber planking from the brig’s hull. But Carl is adamant — a “could be” is not good enough. If he doesn’t sight it, it hasn’t been discovered.

The next few days, the weather turns rough and becomes too dangerous to dive. His holidays over, Carl stows his dive gear and returns to his Army base in Townsville. Shipwreck hunting requires perseverance but most of all, the luxury of time.

“Next year,” he says, with a smile. “I’ll be back to find her next year.”

This story was first published in the February 2019 issue of SALIFE.