Trailblazers in their male-dominated professions, these South Australian women have broken new ground for others to follow. Griefologist Rosemary Wanganeen tells us about the challenges she faced and how she overcame them.

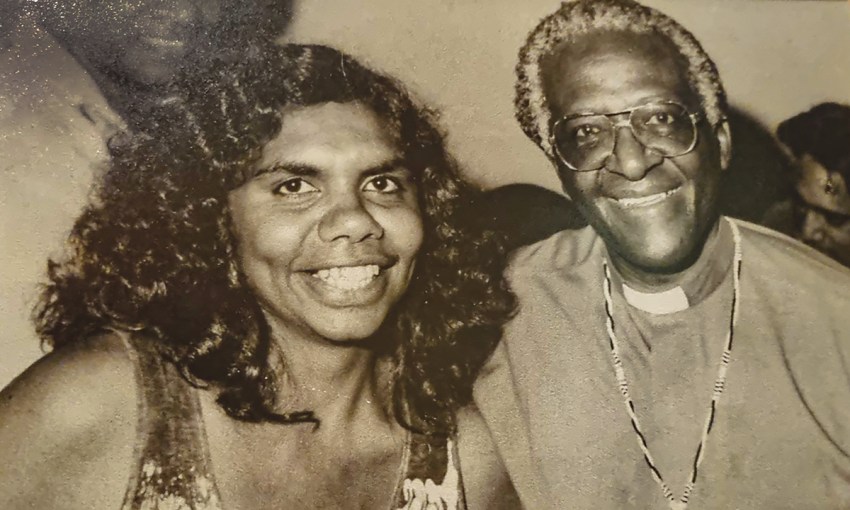

Words of wisdom: Rosemary Wanganeen

Rosemary Wanganeen – Founder of the Healing Centre for Griefology

Can you give us a brief summary of your career?

I’ve worked in the space of health, welfare and social justice for Aboriginal people for nearly 30 years. My career has been motivated by my own experience as a South Australian Aboriginal woman with ancestral links to the Kaurna of the Adelaide Plains and Wirringu from the West Coast. Today, as a Griefologist and Counsellor, I study the human relationship between ancestral losses and their suppressed unresolved grief. I believe Griefology can help people of all cultures to prosper, which is a human right for all. I’m also currently undertaking a Master of Philosophy at the University of Adelaide.

What are you passionate about in the work you do?

My passion for Griefology has exploded into a multitude of life experiences and into many sectors outside of my field of work. My career has not just shattered the glass ceiling as an Aboriginal woman but has also allowed me to intuitively research Griefology across a number of decades.

What were some of the challenges you faced early on in your career?

The most significant challenge or barrier to me thriving as a businesswoman was two pronged: I secretly feared mainstream society because I would experience rejection simply because I am a woman and, worse, a percentage of these rejections would be racially motivated. And two, I would experience rejection from pockets of my Aboriginal community because to become a businesswoman meant “you’re not Aboriginal, you’re becoming too white”. You see, Aboriginal culture was never about starting up and operating a business, hence why I feared success even more than failure. I hope to help other women who are secretly fearful they may not be able to withstand the patriarchal systems, irrespective of their cultural identity.

How did you overcome these challenges?

A couple of years into maintaining the business, I realised my fears of success or failure were not so much external, but internal. I had to change the dialogue of my inner voice from fear of success or failure to knowing that I had a right and responsibility to respectfully own my place in the world. On reflection, any challenges and barriers were not so much external because I had some truly genuine support on the sidelines wanting me to succeed. Here I am in the 28th year of my career, planning for the next 28 years.

What has been the most significant improvement for Aboriginal women during your career?

When I was born in 1955, Aboriginal people were still legally controlled by the government under inhumane policies such as the 1911 Aborigines Act that forced my parents to bring me back to the “mission”. I was five when my family left the “mission” but we were still managed by welfare and at age 10 I became part of the Stolen Generation. My adult children are the first generation born “free citizens”. This proves how far Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal society has come and that Aboriginal women in any profession can forge their own careers with all their needs, wants and desires are at their fingertips.

What is the one piece of advice you would give young women entering professional work today?

To break your glass ceiling, become extremely conscious of the inner voices that have been or could become your personal barriers to finding and maintaining your passion, whatever your cultural background. External barriers could just be a figment of our (female) imagination!

This article first appeared in the March 2022 issue of SALIFE magazine.