Artist and recent OAM recipient Nici Cumpston’s journey to becoming a curator at the Art Gallery of SA included many roles – one of which involved processing crime scene photos.

“You can see something and it can look really beautiful, but what’s the underlying story?”

(Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned this story contains images of deceased persons.)

Where did you grow up?

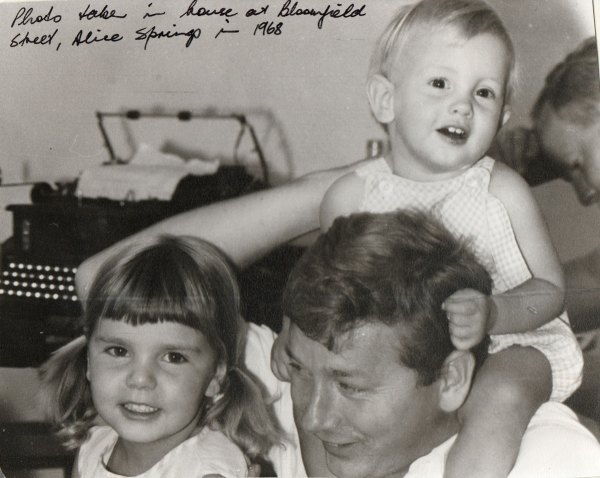

I was born in Adelaide and my parents (Noelene and Trevor) moved to Darwin and then to Alice Springs. My father was a radiographer. It was the early 1960s and there was an outbreak of tuberculosis so he was X-raying in regional communities all through the Territory.

My brother was born in Darwin when I was three-and-a-half, then Dad decided to take up an opportunity to study hospital administration in Canada so we moved to a tiny French village called Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes in Manitoba. We lived in Canada in many different towns, for about nine years.

What was it like moving around so much during your childhood?

We worked out one day, Mum and I, that I went to 17 schools. I learned how to make friends quickly. I really enjoyed the different places we lived and got stuck right in.

I learned how to ice skate in Canada. It was something I had a great passion for and I ended up competing as a figure skater. Every morning you would have to get up early – we were on the ice rink before the hockey players came and cracked the ice up.

Canada was great, but I can’t imagine how difficult it must have been for our mum, with two young children, no family support, in a village that spoke mainly French. At school I was put into the corridor because I couldn’t follow what was happening, but Dad said that within three months I was speaking French.

We lived in several different places in Canada before we returned to Australia. But Australia didn’t recognise Dad’s qualifications and he realised he needed to continue his studies, so we all went back to Canada (by then we also had a little sister, Zena).

We returned again when I was 13. Dad got a job in the Riverland with SA Health, and I went to Glossop High School.

I connected with the Riverland and the river. I would spend a lot of time down at the river and it was a place where I found solace. It wasn’t easy with a Canadian accent as a teenager – the kids were really mean. It was tough being different in a country town.

My sister Amber had been born in Canada, and when I was 17 my sister Olivia was born, but by then we’d moved from the Riverland to Gawler where Dad finally had a job as a hospital administrator.

What did you do when you finished school?

I went back to the Riverland and trained as an enrolled nurse through the Loxton District Hospital then worked at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Nursing was great. I wanted to go on and do the registered nursing training but I tried three times and didn’t get in, so I thought: What’s next?

I moved to the Territory and took a job at the base of Uluru… that was 1984. I worked for a few months as a dishwasher, cleaned the rooms, and was the person who met and greeted the tourists. I also became good friends with the people in the Mutitjulu community, so had really great connections with the Aboriginal people there.

Then I left there to work in Alice Springs and did a course in black and white photography. I had this interest in creating images because my father, as a radiographer, had darkrooms in all our homes and I was the one who would rock the dish to develop the photos – it’s such a magic process.

I started on my journey of photography, really, by travelling through the Northern Territory and into Queensland, doing casual jobs along the way. I just took up whatever opportunity I could. I wanted to interact with Aboriginal people and see the country.

How did photography end up becoming more than a hobby?

My mum was very unwell with a chronic illness so I came back to Adelaide and didn’t know what to do with myself. I had these big bags full of photographs and Mum said: “Well, you could always go to art school and learn how to use your camera properly.”

It was a major stepping stone for me: to take this idea of something that was a hobby, something I loved, and bring it into my daily life. Then I got into art school (the North Adelaide School of Art) and realised there was a whole world of art history and that I could learn about the world through art.

It was such breakthrough, and it was due to Mum. She was the person in our family who took us to plays; she really loved socialising and the theatre, and when we were in Canada she was part of an independent theatre company. She was creative and a great storyteller and I think that’s rubbed off on us kids – we all love the arts and being able to express ourselves.

Tell us about your Aboriginal heritage…

Mum grew up in Broken Hill and her dad had died when she was quite young; he was Afghan Aboriginal. Dad’s father was the head doctor at the New Broken Hill Mines and his mother was a triple-certificate registered nurse; they were very academic, and my parents’ marriage was not something that they were happy about… Mum was Aboriginal and she was pregnant, and it was the 1960s.

I have Barkandji heritage – from the Darling River (in New South Wales). Barkandji means people of the Barka (river).

It’s interesting because over the years, having worked back and forth with my own photographic practice – both in the Riverland and in New South Wales along the Barka, as well as the Murray – I now understand it from more of a cultural perspective. Uncle Badger Bates (artist and Barkandji elder) has helped me to really connect with that part of our heritage and the fact that, ancestrally, Barkandji people would travel and meet up with other language groups all the way along the river systems from Mutawintji National Park along the inland freshwater lakes to the mouth of the Murray.

So those places that I’ve been photographing along the River Murray, ancestrally, are places where our family would have been, and that connection I felt was much more than that I just loved the atmosphere.

You worked for the Police Department when you finished art school – how did you end up there?

My friend saw a job for a darkroom technician with the South Australian Police Department – they were introducing the red-light and the speed cameras and it was all on E6 slide film so they needed someone to manage the processing of that film.

The interview was really intimidating. There were five people in uniform and they were asking me all sorts of questions. “There’s big machinery involved – are you scared of machinery?” It’s like, I’m a nurse, I know about machinery! It was such a learning experience for them and for me because I was the first public servant to be employed within photographics.

I got my work done quite quickly each day so then they would ask me to do the printing of all these images from the crime scene investigations, from accident investigations, from the forensic science … all the images that were then used in court.

It was confronting, and I didn’t know what I was looking at because the only information I had was the name of the victim, the name of the investigating officers, the date of the offence, the type of offence and the film.

I was having nightmares where I was making up stories in my head (about the crimes) and finally I talked to my sergeant and asked if there was anything we could do to help me. So when it was a particularly gruesome case, they would talk to me about it and explain to me where it was and what it was.

I worked there for six years. It taught me how to be really proficient in processing images.

What led you to become an art teacher and then a curator?

I felt that my passion was sharing knowledge with Aboriginal people. They were introducing an advanced diploma at the Tauondi Aboriginal Community College (at Port Adelaide) and needed a photography teacher so I applied and got the job.

That was another real shift in my life. I wanted to be able to empower people to be good photographers. It’s about turning that camera on ourselves as opposed to other people photographing us as Aboriginal people.

I was there 10 years and during that time I also did a Bachelor of Visual Arts (Honours). In 2006 there was a new course being introduced at the University of South Australia – a compulsory course in Indigenous Art, Culture and Design for all of the undergraduate visual art and design students – and I successfully applied for the position to write it and teach it.

Then, in 2008, I got a position as a trainee curator here (at the Art Gallery of South Australia). The first exhibition I worked on was Culture Warriors, which came from the National Gallery of Australia … that was a baptism by fire.

Then I was given the opportunity to curate an exhibition from the collection here – it was called Desert Country and it was shown here in 2010 and then it toured around the country.

That really gave me an insight into what works we had in the collection, but also what information we didn’t have about the works and what works were missing; what were the gaps in these stories and the histories of these works.

I think it’s also important to tell the story about what’s happening today, because Aboriginal culture is ever-evolving. People often want to place things in the past or lament the fact that people are no longer with us, but we have next generations of people and it’s a different story but it’s also a really worthy story.

That’s something that I feel is really important in all that I do through my work here at the gallery (as curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art and artistic director of Tarnanthi), but also in sharing my ongoing connection to my own family’s country and my own family’s stories through the works of art that I create.

You’ve built up a successful practice as an artist and have been exhibiting your work extensively since the late 1990s. What’s your signature technique?

I hand-colour my photographs. I mainly work in black and white and then I go over them with either watercolour, oil paint, crayons or pencils.

How did that evolve?

When I first when to art school, I met the fabulous Kate Breakey, a South Australian photographer who’s lived and worked in the US for 30 years, and one of the things she does is hand colour her photographs.

The Helpmann Academy and the University of South Australia invited her back from the US in the early 2000s as a returning artist for a residency and they invited me to be a mentee.

I had just been creating work for my honours and had these really large-scale photographs which she took one look at and said: “These need to be hand-coloured.” They were of the River Murray in Berri – these beautiful, big, very important grandmother trees; birthing trees. It brought the photos to life and it enabled me to work with colour.

But I don’t just do things one way. I have a work currently at the Adelaide Town Hall in an exhibition (Our Future in the Landscape) and that is a straight colour image. It’s called Oh my Murray Darling.

What are you trying to convey with that image?

It’s a bit of a lament. The connection between the two river systems – the Barka flowing into the Murray at Wentworth, that water has passed through Barkandji country. Throughout the summer of 2018-19 there was no water in the Darling, so people in Wilcannia didn’t have fresh water to drink let alone run their air-conditioners.

So I was thinking about the change that’s happened to the river systems through agricultural practices, through using water as a commodity and the decisions being made about that without any regard for the people living along those waterways – Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

For me, that image was a moment of reflection … the fact that you can see something and it can look really beautiful but what’s the underlying story? That’s in all my work.

What’s your favourite artwork you’ve made?

The Flooded Gum work – it was for a Commonwealth Law Court Commission I did in 2005. I’d been going back and forth to this backwater of the Murray – Eckerts Creek, between Berri and Barmera. An old bushie, a man I’ve known since I was quite young, guided me to this particular spot. He said: “Walk to the end of that trail and you’ll find the most amazing tree.”

They’d spent $10,000 in diesel to pump water into this old forest area of river red gums, so the tree was floating in this beautiful waterway and you could see all the way to where that water met up with the creek.

It was just a moment in time. I kept going back to this tree – photographing it early morning, late afternoon and just getting a sense of it.

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve faced – or continue to face?

One of the biggest challenges is in the role I play as an educator, and as an advocate for Aboriginal people. It’s with me every day, and I feel a deep responsibility, not only through my own family but for the collection, for the artists that we represent and for us to get it right as a nation – to be able to support Aboriginal people to have self-empowerment, to be able to ensure that Aboriginal people have a voice that’s listened to in all levels of engagement.

I’ve felt that since I was young and we came back to Australia. As a young girl, I didn’t really know who my family were because we lived in Canada. So when we came back to Australia and we were in Menindee with our family in New South Wales, I remember this moment, and I would have been about 11, and we were in the store and my cousin Leasa was there and the shop owner completely ignored her and asked me what I wanted.

I looked at Leasa and said, “Leasa’s first – we’re together.” But he wouldn’t serve her because she was a dark-skinned Aboriginal person. And this is the town she lived in; a town of just 900 people and it was the only store. I thought, this can’t be right.

Who’s been the greatest influence in your life?

Mum and Dad were really influential for me – not that I would have admitted it growing up. I was steered in the right direction without even realising the importance of that at the time.

They both passed away very young – Mum was 53 and Dad was 62 – but their spirit is with me, with all of us in my family, every day. We really honour our parents.

Do you have a partner?

Yes – his name’s Jon. We met when we were young; his sister and I nursed together and we’re still besties. He went off and got married, and I had a boyfriend back then. But we met up again about 10 years ago and something clicked.

He works as a surveyor. Since we’ve been together he’s been to uni and studied social science; he really loves policy and things that make my hair curl!

Where are you likely to be found when you’re not working?

I just love being out on country. Being with my family, being able to walk around the bush, and my favourite thing is taking photographs. I take my camera everywhere.

How did you feel when you were awarded an Order of Australia (OAM) in the recent Queen’s Birthday honours?

I was so shocked! But the thing that means the most to me is that I was nominated by the elders from Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands – and that five of their artists also got one, so I feel like I’m in good company.

My Aunty Marie, my mum’s eldest sister, who was living in Menindee, she was awarded an OAM in 1988. She started Nyampa Aboriginal Housing – the people were all moved off the mission when the referendum happened and were living on the river in humpies and she thought it was ridiculous. Her husband Jack died, she was pregnant with their ninth child and she was living in a humpy. She was a very strong-willed person so she supported that whole community to get housing. That then developed into programs for unemployed people.

She was incredible and all of her children are as incredible as her. My cousin Fiona Kelly is now the principal at the Menindee Central School, so really great stories have come out of that leadership that she encouraged in all of her children and in us as family.

So that also helped me to embrace it (my OAM). It is amazing; I would never have thought I would end up with what Aunty Marie got for all her work. Whenever we visited we’d always say, “Show us your medal, Aunty Marie!”

My South Australian Life is a first-person series, published each Sunday. Read our previous profiles here.