At the peak of harvest time in stone fruit country, SALIFE meets a third-generation apricot grower at Renmark where some things are still done the old-fashioned way.

Ripe for the picking

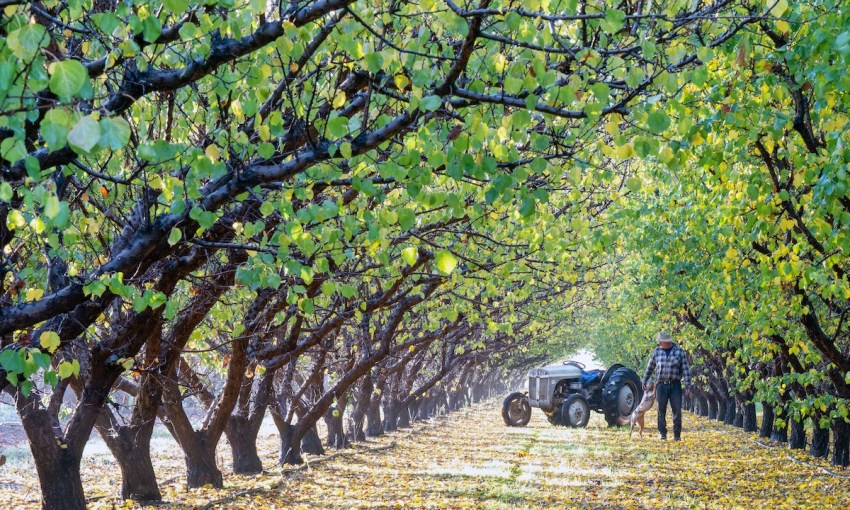

Trundling down a long arboreal archway on his vintage tractor, fruit grower Philip Glatz looks up to study his apricot trees that reach way out overhead, as if striving to touch branches with their neighbours across the row.

It’s a leafy avenue that Philip has been inspecting for 42 years; tending to his Renmark orchard just as his father and grandfather did before him.

In spring, the bare branches are sheathed in pink and white blossoms. In summer, the canopy swells green with apricots ripening in golden clusters. Then, Philip’s favourite season is autumn when the ground is blanketed in yellow leaf-fall.

But it’s not the leaves Philip loves most about autumn; “You can sleep in,” he laughs. “I’m not a morning person. That goes against everything about farmers and fruit growers because you’re meant to be morning people.”

Despite his aversion to mornings, Philip was destined to be a fruit grower. “I always knew I was going to be a blocky [a fruit block owner]; it’s my calling,” says Philip.

“I like growing things and looking after things. I also enjoy growing veggies and developing new areas of the property. My grandfather was a wheat farmer in Victoria, and he came to Renmark and bought this property in 1942. My family has been here now for 80 years.”

The farm was founded by one of the area’s first physicians over 100 years ago. Some of Philip’s apricot trees are close to half-a-century old but there are a few pear trees twice that age.

“I left school to work full-time on the block in 1980 when apricots were widely grown in the region. Since then, they’ve very much contracted in the area and there are far fewer apricot growers these days,” he says.

“Properties like mine used to be classed as ‘fruit salad properties’ that grew many different varieties, but the industry has shifted towards monoculture, growing single crops, such as vines or almonds.

“There are fewer mixed fruit properties around today.”

These days, Philip is a one-man show and exists in a liminal space between old and new, exemplified by his old tractor, a 1954 Little Grey Fergie – a model more popular among collectors than farmers.

When he picks his apricots, they are placed in anachronistic metal containers – “dip tins” – that are old relics from when the farm produced sultanas.

Philip also shies away from email, preferring to stick with his fax machine. A few things have changed, though. Back in the 1980s, South Australia produced the lion’s share of the country’s dried apricots.

Today, Victoria produces twice the volume as South Australia.

Like other stone fruit, apricots are sensitive and perishable crops that require plenty of labour.

Philip, however, continues to put in the hard work and in recent years he has scaled back his orchard to a manageable size that he can mostly look after himself. Sadly, it has meant ripping out some century-old fruit trees.

“Up to a few years ago, some of the pears were 100 years old. Now, I’ve got just a couple of them left – if Dad knew, he would turn in his grave,” laughs Philip.

“The backpackers dried up about five years ago and I’ve scaled the farm back to be a one-man operation with fewer overheads and inputs. I’ve cut my pears and apricots in half so now I’m a micro-business, focusing on the premium side of things.”

The apricot orchard comes into fruit from early December through to mid-January.

Philip normally produces two tonnes of dried apricots over summer and his main varieties are River Rubies, River Brights, Mysteries and Storeys.

This season, however, apricot yields are down because of high rainfall weather events which have created damp conditions and a late season.

Input costs have also increased this year, but Philip takes the good with the bad.

“You pick apricots when they are the right colour. I start early in the morning and they’re big 12-hour days but I enjoy working on my own.

“I have had extensive help from my family over the years, too,” he says.

The metal tins full of apricots are placed into a cool room.

Then, they are cut and pitted by hand, preserved with sulphur dioxide and placed onto wooden trays to dry in the sun for a few hours.

Before drying, Philip’s apricots are cut by hand, not by machine, which means he can pick them when they’re riper, juicier and sweeter.

Along with being sweet eating, apricots carry a nostalgic link for people who grew up with apricot trees or can remember when they were more widely grown.

Philip says it’s a shame that he’s had to reduce the size of his orchard, but some things do have to change with the times.

“Life is all about change, and I don’t like change,” he laughs.

This story first appeared in the November 2022 edition of SALIFE Magazine.